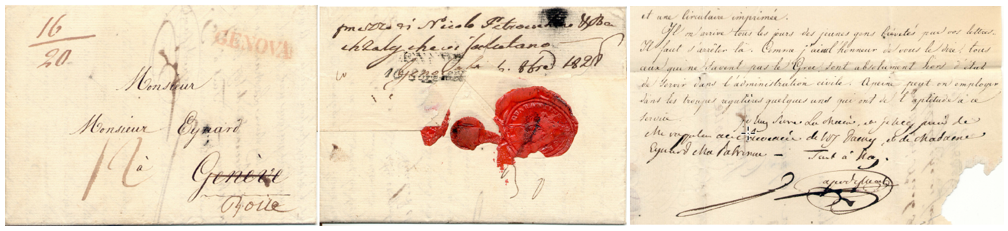

The destruction of Psara, Suzanne Elisabeth Eynard (1775-1844), sister-in-law of the great Philhellene and friend of I. Kapodistrias, Jean Gabriel Eynard (SHP Collection)

George Argyrakos – June 2020

I should start this article as Socrates and Antisthenes suggested, with an “investigation of the terms”.[1] Philhellene (φιλέλλην) today literally means a person who loves or is friend of Greeks or Greece. In Herodotus (5th century BC), we find the first reference to a philhellene, the Egyptian pharaoh, Amasis II (6th century BC). In antiquity the same term had the additional meaning of a Greek patriot, which is why Xenophon (in Agesilaus 7.4) refers to the Spartan General Agesilaus as a ‘philhellene’. The antonym was mishellene (μισέλλην), and Xenophon was the first to contrast these two terms in one sentence, referring to Egyptian leaders, some of whom were philhellenes and others mishellenes (Agesilaus, 2.31). Many other important figures of classical and Roman antiquity are referred to as philhellenes (among them Nero), but infinitely more are those who in practice were friends of Hellenism or the Greeks, although are not conventionally described as philhellenes (but there were also hellenising persons, and later grecomans, grecomania, and hellenists). As two distinct geocultural entities were gradually formed around the Mediterranean (especially after the spread of Islam), philhellenism was confined mainly in the Eurasian area north of the Mediterranean, but after the 11th century spread to Russia, and after the 18th century could be found in whole of America. There was a long period when the term was not used because “Hellen” (Έλλην) or “Greek” had acquired the meaning of “pagan”. During the Greek Revolution of 1821-29 it again came into use, from which the term “philhellenism” was formed some time in 19th century.

Dominant historiography traces the robust restoration of classical education in Europe during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. That period coincides roughly with the birth and development of the printing industry, which functioned as an enhancer of a pre-existing trend, found at least in the scholastic philosophy and theology of the Middle Ages. It is indicative that there were about 590 editions of works of Aristotle with their commentaries by the year 1500, when typography was still in its infancy. In the region of the Byzantine Empire, for historical and cultural reasons, philhellenism (of Greeks or others) took a different course and form, as sections of the Byzantine subjects gradually developed a Greek national (or pre-national) identity after the 13th century.[2] Modern historiography has revised its views about a “theocratic Byzantium” that was supposedly hostile to Hellenism, and revealed that hellenophilia did not decline during the Byzantine period. For the purposes of this article, the kind of the relationship that the Byzantines had with antiquity, i.e. whether it was mimicry, romanticism, consciousness of continuity etc. does not really matter, besides remaining a subject of scientific controversy.[3] What does matter here is that, in one way or another, a contact with classical and hellenistic antiquity was maintained, which had consequences on an Eurasian scale, mainly through the relations with the Slavs.

In this article, I argue that the Philhellenism (with capital “P”) of 1821 became possible mainly due to the following factors: (a) the common cultural background of Greeks and Europeans (including the Russians), (b) the wide use of printed material and especially of newspapers, and (c) the persistence of the Greeks in their struggle and their sacrifice.

It is almost self-evident that Philhellenism would not have flourished during the Revolution, had there not been a Greek cultural substrate in the Western / Christian world. Christian Serbs also revolted shortly before 1821, as did other Balkan ethnicities later, but there was no “philo-serbianism” (except in Russia) or “phil-albanianism” etc., let alone to an extent comparable to Philhellenism. Also, by definition, there would be no Philhellenism if the revolutionaries had not declared and felt themselves Greeks (“We are the Greek nation of Christians…”, Declaration of Patras, March 26, 1821) and if this had not been obvious to third parties due to the use of the Greek language and the continuous habitation in the historical Greek lands. These obvious elements of national identity, coupled with the resistance of the revolutionaries in a long bloody struggle, played a huge role in the emergence of the philhellenic movement, which turned the political balance decisively in favor of Greek independence.

Among the various forms of Philhellenism, the conscription of volunteer fighters, the literary and artistic works, and the aid in money and supplies by philhellenic organizations have been extensively acknowledged, mostly in relation to Western Europe and the USA. Here I will refer to some aspects of Philhellenism that are usually only mentioned in academic works, such as Russia’s very important philhellenic activity, and the interest of the international anti-slavery movement in the slavery of the Greeks.

The Revolution was declared six years after the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), from which Europe had suffered enormous human and material loss and political upheaval. The direct and indirect casualties were between 3 and 6 million deaths (military and civilians), at a time when the population of Europe was 3 or 4 times smaller than today. By the end of the wars, the foundations were laid for an international dialogue as the European states aimed at peace and stability. The Congress of Vienna (1814-15) and the formation of the Holy Alliance inaugurated this policy that today is considered as practically compulsory. In Eastern Europe, Russia had emerged as a Great Power, and the West’s concern was that the Greek Revolution could mobilize a new Russo-Turkish war, which in turn would bring about geopolitical reshuffles and possibly a new great European war. Due to this situation, in the first months of the Revolution, the European governments and much of their public opinion were indifferent to negative towards this uprising. The factions who were potentially philhellenic were in the minority, and in some countries were suppressed by the censorship of reactionary governments, such as that of Metternich, who controlled not only Austria but also much of the German-speaking world, part of Italy, the Vatican, and parts of the Balkans.

Despite initial European assumptions and the hopes of the Greeks, Russia did not help the rebels militarily, which led to the failure of Alexander Ypsilantis’ insurrection in Moldavia and Wallachia. The reasons for this Russian policy were mainly the above mentioned international conditions, the influence that Metternich exerted over the tsar, and Russia’s internal political problems. However, contrary to popular belief, in the background, Russian diplomacy showed a willingness for international intervention in favor of the Greeks. Ιn July 1821, the tsar proposed an alliance with the French in order to make Greece a French protectorate, and a similar proposal was directed to the other Powers in September. The Russian argument was that “from the Bosphorus to Gibraltar there is space for all“. However, the tsar was met with rejection by all the other Powers, which all feared each other and especially Russia. The latter proposed a similar plan in January 1824.[4] The protagonists of the philhellenic Russian faction were Ioannes Kapodistrias (until his resignation in August 1822), and his less-known co-worker Alexandros Stourtzas.

Fortunately, the tsar was not the only pole of power in Russia. The Russian Orthodox Church, the army and several politicians and nobles, including members of the royal family, formed the so-called “war party”. In other words, there was a robust philhellenic pyramid with a wide popular base and a peak reaching into the palace. Researchers of Russian policy and the Revolution believe that Russia had a double-sided approach, pursuing a formal and an informal policy simultaneously, or else, that Russia was viewing the civilian Greeks as Orthodox brothers, and the revolutionaries as dangerous elements. [5], [6] What exactly happened in the top echelons of the Russian government and the palace remains almost unknown, due to the difficulty in studying the Russian archives. According to the well-known sources, however, it is clear that two facts saved the Revolution: first, the constant threat of a Russian invasion of the Ottoman Empire, and second, the support for the Greeks by the Russian Church and the Russian people. Compared to the policies of other powers, it seems that Russia was the only state that indirectly supported the Revolution in the early years, when the rest practically supported the Ottomans. Russia’s official turn towards active Greek support began in the early 1824, when she proposed a semi-autonomous Greece, similar to the Danubian Hegemonies, to the other Powers. Greek leaders learned of this proposal from the French newspaper Constitutionnel (31-5-1824, New Calendar); they were not prepared to accept the idea of incomplete independence, and most of them suggested that they ask for British protection. It was feared that Russian influence would make Greece an absolute monarchy under the rule of the Phanariotes, instead of which they would prefer a constitutional western-style monarchy. This decision by the Greeks caused a deterioration in their relations with Russia.

It is self-evident that the philhellenic disposition of the Russians was based mainly on religious and historical ties, as well as on the existence of a common enemy. On a secondary level, liberal circles, such as the Decembrists, felt for the social aspects of the Revolution.[7] Patriarch Gregory V’s execution caused a great shock and interest among the Russian public. Compared to western Philhellenism, the Russian version was more “multi-collective”, based not only on classical education, but also on the Byzantine, post-Byzantine and contemporary experiences. The latter included lively interest and relations with sacred sites such as Mount Athos, Jerusalem and the Eastern patriarchates, places with a strong Greek character that functioned as centers of a pan-Orthodox transnational space. The Russians knew the Greek and wider Balkan genealogy of anti-Turkish resistance, which even had phases of cooperation such as the revolution of 1770 (Orlov Revolt), better than Westerners.[8] Probably through Mount Athos they learned about the Greek Orthodox new-martyr saints, a specific phenomenon of anti-Islamic resistance and cryptochristianism, which was almost unknown in Russia till the 18th century.[9] They almost certainly knew the anti-Islamic messianic literature of Byzantium, which dates back to the 8th century.[10] This long anti-Islamic Greek resistance (or non-capitulation) was utilized by Russia’s “war party” as reasoning in international law: a crucial point in history was Constantinople’s non-capitulation in 1453. Kapodistrias and Stourtza, in order to dispel the tsar’s doubts about the legitimacy of the Revolution, argued that “the Greeks never swore allegiance to the sultan; [and] they revolted against an illegitimate monarch.”[11]

Unfortunately, 20th century Greek historiography has avoided adequately elucidating Russia’s role, due to various political expediencies, i.e. the western influence on Greece, the Cold War, and later the domination of a historiographical school stuck to the theories of “neoteric” ethnogenesis. For the same reasons, the pre-19th century Greek or Christian uprisings were allowed to be forgotten and historiographically distanced from the 1821 Revolution. Until the 1990s, there were relatively very few studies, such as those of Gregory Ars,[12] Theofilos Prousis, and Dimitris Loules,[13] [14] that highlighted Russia’s role in the Revolution. Recently, however, there has been increased interest in the subject, and many modern publications have appeared, thanks to the opening of Russian archives.

In fact, Russia saved the Revolution and many Christian civilians by taking the following actions: In brief: from the beginning of the Revolution, strong Russian forces took up positions along the left bank of the Pruth river, which was the border with Wallachia and Moldavia (today the Romania – Moldova border). In July 1821, the Russian ambassador to Constantinople delivered the first note of indirect support of the Greeks to the sultan, invoking the previous Russian-Turkish treaties. It was an ultimatum, most likely a work of Kapodistrias and Stourtza. With this, Russia declared that, according to the treaties, she was the protector of the Christians and demanded the withdrawal of the Turks from the Danubian Hegemonies, as well as respect for the civilian Christians and their property.[15] As a result, Turkish retaliation against the Greeks of Constantinople and other areas was mitigated. The sultan took seriously not only the Russian demands but also the advice of the Western ambassadors who warned him that a Russian invasion could not be ruled out. The expectation of such an invasion was pervasive throughout the body of European society, that is, the people, the commercial and banking houses, the intellectuals and the politicians, and it was a daily theme in the news. The rumored Russian attack did not happen until 1828, but was constantly on the table, forcing the Ottomans to maintain strong forces on the Pruth border, on the right bank of the Danube, and around the capital. Essentially, the larger and better organized Turkish army was tied up away from rebellious southern Greece, in which the Empire could afford to only deploy small forces. This literally saved the Revolution until the Great Powers changed their policy.

At the same time, inside Russia, government officials and the Church organized a large-scale humanitarian aid program for the Greeks. This was supported by all social groups and indeed by the large agrarian mass of Christian Russians who were illiterate with no classical education. Theophilus Prusis (1985) describes this movement as “philorthodox” (φιλορθόδοξο). From the first months of the Revolution, tens of thousands of Greek refugees from Romania, Constantinople, etc. sought safety in Russian territory, “salvaging only their life and the honor of their women and children”.” In July 1821, Tsar Alexander approved the aid program for the Greeks who took refuge in Odessa and Bessarabia. Other Greeks, who already lived there, also offered great help. The program was initiated by Prince and Minister Alexander Nikolayevich Golitsyn, who explicitly acknowledged the moral obligation of Russia and Western Europe “to render help to the sons of that country which fostered enlightenment in Europe and to which Russia is even more obliged having borrowed from it the enlightenment of faith, which firmly established the saving banner of the gospels on the ruins of paganism.” Millions of rubles were raised from all parts of Russia and from all social classes.[16]

The February 19, 1827 issue of the German newspaper Allgemeine Zeitung presents a complete account of the financial aid sent to Greece during the years 1825 and 1826.

The philhellenic movement in the West and probably in Russia as well[17] was fueled, among other things, by the publicity the Revolution received via the newspapers and Greek heroism and sacrifice. The latter factor is underestimated by academic historiography for the sake of more “modern” socio-economic analyzes, free of heroes and martyrs. The reality is that if the revolutionaries had not been able to resist until the winter of 1822-23, Philhellenism would have had no object. I will attempt to explain this, by making a parallel indicative presentation of news from European newspapers of the time, which were the main media of opinion-making. I will refer mainly to the French-language Gazette de Lausanne (hereinafter GdL), a Swiss philhellenic newspaper that often reproduced news from other major newspapers.[18] It is to be remembered that until the Revolution, no newspapers were published in the Ottoman Empire, neither in Greek nor Turkish.

The first news on Ypsilantis’ movement in Wallachia appeared in the newspapers at the end of March 1821, and quickly took place next to the news on the political revolutions in Naples, Piedmont, Spain and Latin America. On May 1st, 1821 (all dates in New Calendar), the front page of the GdL writes about the first Greeks taking refuge in Russia and the foreign embassies of Constantinople.[19] Like many other newspapers, it publishes one of Ypsilantis’ proclamations, the well-known “Fight for Faith and Motherland. The whole motto is of late-Byzantine origin, as it is contained in the last speech (allocution) of Emperor Constantine Paleologos before the fall of Constantinople, as mentioned by George Frantzis in his chronicle (1477).[20] It is also found (but not as a single sentence) in excerpts from speeches by the same emperor, written in Russian by the chronicler Nestor-Iskender, a contemporary of the Siege of Constantinople.[21] Almost in its familiar form, the motto is attributed to Peter the Great, and was later used in Russia with minor variations until the time of the Revolution. Ypsilantis obviously learned it while serving in the Russian army; at that time, it was standardized as “For the faith, the Tsar and the Motherland.” (Za veru, tsarja i otéchestvo).[22] Ypsilantis’ proclamation closes with references to heroic ancient figures and events, well-known to Europeans and already used as symbols of political ideas: Thermopylae, Miltiades, Leonidas, Athens, struggles against tyrants and Persians, etc. These and other classical names often appeared in the news about the Revolution, as the events of the war actually took place in areas with classical toponyms, unchanged since antiquity. Due to its high symbolism, Thermopylae was particularly often mentioned in the news, even when it was not directly related to the events. The “obsession” of Europeans with Thermopylae began in 1737 with the very popular epic poem “Leonidas” by the English poet and politician Richard Glover, which was an allegory for the contemporary demands for more political liberties.[23]

After the first and rather confusing news in which the Greek Revolution is related to those in Naples, Spain or South America, a clearer picture emerges. In the edition of May 8, 1821, GdL states that this is not a political revolution but a clash of nations, religions and cultures. It points to a key feature of the Revolution: Greeks are not demanding government reforms, but independence and liberation from their yoke. Many papers describe scenes of a religious war: priests precede the fighters with crosses and icons, the flags bear the cross and images of saints, warriors swear by the Gospel. The leading bishop of the Peloponnese -Germanos of Patras- and other hierarchs, ignite the spirits of the warriors and take part in fights and sieges (GdL 1/6/1821) (all dates in DD/MM/YYYY form). Some newspapers publish a revolutionary speech by archbishop Germanos in the monastery of Hagia Lavra near Calavryta (Constitutionnel of Paris, 6/6/21, Times of London 11/6/21 etc.)[24]. Muslims, too, are fighting a religious war, with their own religious leaders blessing the warriors, raising the Prophet’s war flag, and invoking the Quran and the salvation of Islam (GdL 8/6/1821, 1/1, 26/4 and 24/5/1822). The news on the execution of the Patriarch on the Easter Sunday (22/4/1821 N.C.), and the massacre of many Greeks (and Armenians) in Constantinople, Smyrna and Kydonia (Ayvalik) also make a vivid impression (GdL 29/5, 5/6, 15/6, 31/7/1821 etc). Christians are tied up and thrown into the sea to drown, so that no blood is shed on the feast of Ramadan (GdL, 3 and 7/8/1821). Bags full of heads, ears, noses and tongues of Greeks are sent to Constantinople (GdL, 7 and 21/8/21).[25] The national-religious character of the Revolution is confirmed by reports from the British Embassy in Istanbul.[26] Such news activates the religious and cultural reflexes of Europeans. Despite dogmatic differences, Catholics and Protestants do not remain impassive, as the events have a “unifying” character, referring to the age of the first martyrs, long before the Schism. In this regard, Western and Eastern Orthodox Churches speak the same language: correspondence from Greece says that Greek priests consider all women who were dishonored by the Turks as martyrs (GdL 4/1/1822).

Soon the first journalistic comments and exhortations for philhellenic governmental policies appear.[27] On 8/6/21 GdL writes that an operation to destroy the formidable Turkish force would be compatible with European policies for the protection of peoples from invaders. On June 22, 1821, it says that it is the duty of Christian Europe and a matter of honor for Christianity and humanity to put an end to the persecution of the Christians of Constantinople. Anti-Greek (or anti-revolution) newspapers such as the Oesterreichische Beobachter (Austrian Observer, effectively an organ of the government of Vienna) highlight some negative aspects of the Revolution, like the Romanians turning against Ypsilantis and the alleged connections of the Fraternal Society (Φιλική Εταιρεία) with similar secret societies in Europe (GdL, 22/6/21), but these do not significantly change the overall picture or mood. Oesterreichische Beobachter and other German papers publish some revolutionary declarations and speeches, as well. For example, in the first days of June 1821, Algemeine Preussische Staat Zeitung presents the revolutionary proclamation of the so-called Messenian Senate, news about the massacres in Constantinople and Izmir, the insurgency in Morea under the leadership of the archbishop and the priests, and the execution of the Patriarch.[28] Some German and Swiss newspapers call on readers to offer financial and military assistance.[29] Very early on, German-speaking intellectuals took a position in favor of the Revolution, as did much of German public opinion. Poet Wilhelm Müller responds with a poem to the Austrian Observer on behalf of the Greeks. Unfortunately, censorship and bans have suppressed many philhellenic activities in Germany, and limited the information we have about them.[30] Where there is no censorship (mainly in Britain and the United States), Philhellenism is freely expressed, nourished by the centuries-old background of Greek education, something that Percy Shelley summed up in four words: “We are all Greeks.” Newspapers that were originally anti-Greek, such as the Gazette de France and Drapeau Blanc, are gradually leaning towards the Greeks under the influence of personalities such as François-René de Chateaubriand,[31] who in a letter to a news publisher wrote in 1826: “Regardless of what happens, I want to die a Greek.”[32]. There are a number of studies on the theme of European journalism and the Revolution, starting with the ground-breaking works of I. Dimakis and Aristides Dimopoulos in 1960s.[33]

The frustration and suffering of many Philhellenes from their contact with the Greek reality, especially in the first three years, is well known. Most of them were enthusiastic but not military-trained and hardened, nor could they understand the Greeks. The latter, on the other hand, could not understand the Europeans. As Lord Byron wrote, most Philhellenes knew nothing but etiquette, squabbling over ceremonies and regulations observed in their homelands.[34] It is unclear though, whether all Philhellenes observed the European “savoir vivre” and if they really were disappointed in Greece. It seems that some of them adapted well to the circumstances. For example, we are informed in some Philhellenes’ memoirs that after the fall of Tripoli (in Morea) most of them were flanked by young Turkish women, and notably an Italian kept a harem of 10 Turkish and Greek women.[35] Other Philhellenes admired the resilience of Greek fighters with reference to long military journeys and hardships, and their austerity of diet and living habits. Objective and educated Philhellenes and travelers notice that the new Greeks observe Homeric cultural practices, such as washing hands before a banquet, a habit not necessarily followed by all Europeans, as they note.[36]

In June 1821 the first news appeared of the advance of Russian forces to the border of Pruth and in the Aegean (GdL, June 5, 19, 22, July 6 & 27, August 21 & 28, 1821 etc.). Then there was almost daily news of an impending Russian invasion of Ottoman lands, and sometimes it was even said that the invasion had begun. It was also reported that the Austrian army was reinforced on the border with the Ottoman Empire, preparing for any act of war. The news, while not always accurate, was of concern to Europeans who did not want to experience a new war. Certainly, the same news was reaching the Sublime Porte. At the same time, it was realized that the policy of strict neutrality was not the only choice, since Russia was threatening to intervene in favor of the Christians. On 29/6/1821, GdL writes that, as a reaction to the persecution of Christians and the destruction of churches, the Russian ambassador delivered a note to the Porte about the violation of the Treaty of Bucharest (1812). On the same page, an excerpt from Chateaubriand’s “Travels in Greece …” (1811) which describes the extermination of Morea (Peloponnese) by the Albanians after the Orlov revolution of 1770 was published. On 11/9/1821, it summarizes the restrictions and humiliations that Islamic law had imposed on non-Muslims over time. Russian demands for the respect of Christians are often repeated in the news.

Especially in countries with parliaments such as Britain and France, public opinion had a considerable political influence. Opposition lawmakers were raising issues in the parliaments pressing governments to take a stand (e.g. MP’s question in the British Parliament, GdL 3/7/21). Even outside the organs of the states, other centers of power such as the Protestant Churches and intellectuals were activated in favor of the Greek cause. On 1/7/1821, the first minor philhellenic movement in Britain was announced (GdL 10/8/1821): until then, ships from North Africa (nominally part or the Ottoman Empire) had been carrying out raids against the Greek fleet and, when in difficulty, they resorted for protection and resupply to Ionian ports that were under British administration (Turkish ships were doing the same). Greek ships, as deprived of any international legitimacy, could not approach British ports. However, in the summer of 1821, Britain reactivated an earlier treaty of 1800, according to which North African ships must keep a distance of 40 miles from the Ionian Islands. The patriotism of the Greek Ionian also counted here because, despite the bans, thousands of them were passing to mainland Greece to fight or were engaged in other philhellenic activities, troubling British rule. At that time the first serious discussions on the “Eastern Question” started, which essentially ended after the First World War. The Courier of London, which echoes the government position, on 30/7/21 raises the issue of the dissolution and succession of the Ottoman Empire, expressing itself positively in favor of the independence of the Greeks (GdL 10/8/21). Correspondence from London has that “the pressure of public opinion from all over England starts producing results” (GdL 4/1/1822).

The presence of Philhellene fighters in Greece was only one of the expressions of Philhellenism; it was the most heroic and sensational, but not necessarily the most effective. Some of them really loved Greece, and others were more of professional soldiers, veterans of the Napoleonic Wars looking for a new career. They showed true heroism and many became “martyrs” (that is “witness”) of Philhellenism. Although their numbers were relatively small, they played an important role in some battles. Also, we owe a lot to the memoirs written by some, and to the news they sent to Europe and the United States in correspondence from Greece.[37] Gatherings and departures of Philhellenes for Greece are frequently described, such as the departure of a ship from Marseilles under the blessings of the local Orthodox bishop (GdL 17 & 24/8/1821), the preparations of German Philhellenes (GdL, 4, 11 & 14/9/’21, etc.), the departure of Germans and French under General Norman (GdL, 1 & 8/2/1822), etc.

From the Roman era and the Crusades onwards, philhellenism has had the side effect of plundering Greek works of art. This endeavor of collecting Greek antiquities from southern Italy and Greece continued during the Renaissance, but also in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Vatican, for example, was one of the largest collectors of antiquities, studied there by hellenists such as Johann Joachim Winkelman (1717-68), the founder of scientific archeology, who gave impetus to the current of neoclassicism and romanticism, which in turn gave birth to 19th-century Philhellenism. This kind of modern abduction of Europa created small centers of hellenism in Europe which, among other effects, played a positive role in the formation of the philhellenic movement. Fortunately, apart from this controversial artistic paradigm of transporting antiquities to Europe, there were also some positive, although less known interventions for the in situ antiquities: in 1821, at the request of the British ambassador in Constantinople, Lord Strangford, the Grand Vizier (the Ottoman equivalent of the prime minister) gave a stern order to the Ottoman army on its way to recapture Athens, to respect the ancient monuments “which have at all times been highly interesting to the learned in Europe“.[38] It is possible that this action saved some of the monuments, and it is worth mentioning along with any other references to Elgin.[39]

The July 27, 1821 issue of the Journal des Debats refers to the work of a Frenchman who recorded the cultural monuments of Athens in detail, expressing fear of the damage that could be inflicted by military operations. (EEF Collection).

From the middle of 1821 there was a change in the political climate in favor of the Greeks, at least at the level of public opinion, the intellectuals and certain political circles. But if this climate was to have a real impact, the revolutionaries had to hold out on the battlefield. If they had laid down their arms in exchange for the pardon promised by the Turks, any philhellenic movement would have no objectives. The occupation of Tripoli (capital of Peloponnese) in September 1821 was of decisive importance, as well as the practical demonstration that the Greek fleet could successfully confront the Turkish one. At that time, hostilities were mainly taking place between spring and autumn, while winter was a period of regrouping. Greeks, with heavy losses of fighters and civilians, successfully kept a substantial area of land and sea in Southern Greece under control until the winter of 1821-22. The aspirations of the Turks and the counter-revolutionary circles in Europe were postponed to the next spring.

Year 1822 did not start well for the Revolution. The rebellious Ali Pasha of Ioannina was defeated and killed, which freed up considerable Ottoman forces from Epirus. However, on the battlefields, the fighters still resisted well. The destruction of Dramalis’ Ottoman army in Morea in the summer was decisive, and showed that even in 1822 the Revolution would not be extinguished. The same year an unfortunate Greek campaign in Epirus was organized, where at least 60 Philhellenes were killed in the battle of Peta. This military corps, organized by French Philhellene Georges Baleste, fought heroically but the battle was lost, either by betrayal or because of strategic mistakes.

The great massacre of Chios in March 1822 gave a great boost to the philhellenic movement. Thousands of Greeks were slaughtered by the Turks and many others were sold as slaves, with almost no voluntary conversion (“turkification”). Like all other newspapers, GdL, on 21 and 28/5/1822, reports scenes of arson and massacres on Chios. It writes that the dead exceeded 50,000 and that the Turks of Smyrna passed by in boats to loot Chios. In other news, ships struggled to navigate in the port of Chios because the sea was clogged up by floating bodies. The French ambassador heroically rescued a few hundred women and children. It was believed by some that the massacre would trigger Russia’s intervention (GdL 7/6/22). Thousands of women and children were transported and sold in the bazaars of Constantinople, and many committed suicide on the way. “No battle of the last wars has caused as much bloodshed as Captain Pasha’s landing in Chios. A war that would stop this bloodshed would be justified” (GdL 11/6/22). News about similar atrocities in Bulgaria was also published.[40] “More than 2,000 severed heads, noses and ears were sent in bags to Istanbul and about 6,000 women were sold through auction to Jews who paid 4 to 15 piastres for each victim. Young boys underwent compulsory circumcision and were given to Turks”. “There is indignation for the European politicians who are watching indifferent the massacre of Greek Christians.”(GdL 25/6/22). The massacre of Chios became known all over the world due to the newspapers, and later by Delacroix’ emblematic painting of it. The mass capture and slavery of Greeks was not something new. It was carried out systematically from the beginning to the end of the Revolution, and had a significant impact on the feelings of European people and the policies of governments. The fact that the European public opinion had not paid much attention to the previous massacre of the Turks in Tripoli simply shows that the feelings were clearly in favor of the Greeks, while the Turks were considered conquerors and illegitimate perpetrators (hence called “Hagarenes, children of Hagar or Ismaelites” by the Greeks). In fact, the news and other texts of the time often explain that while the acts of violence by Greeks against the Turks were committed by an angry mob, the massacres of the Turks were organized by the state.

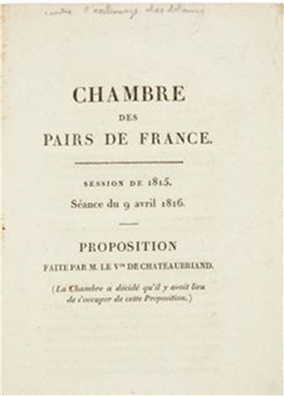

The slavery of the Greeks was a major humanitarian disaster, and one of the factors that forced politicians to act. From the second half of the 18th century, the abolitionist movement was on the rise in Europe and North America, and legal measures were gradually taken to abolish the ancient practice of slavery. In 1807 Britain and USA banned the slave trade, and in 1833 slavery was generally banned in Britain.

Proposal by Chateaubriand, in favor of the abolition of slavery of Christian populations, in the French Parliament of 1816. This proposal, which passed, refers to the rights of humanity and the deletion of this shame from Europe (EEF Collection).

At the time of the Greek Revolution, British ships were patrolling the oceans, capturing ships carrying slaves and liberating them, as well as forcing African chieftains to stop selling people.[41] The protagonists of the anti-slavery movement were roughly the same circles that were favorable to the Revolution, that is, Protestant Churches, and politicians from all sides, from liberals to conservatives. In many newspapers there were separate columns with news on the abolitionist movement.

In this climate, the reports that Christians of the East were sold like animals in the bazaars of Constantinople, Izmir, Alexandria etc., came as a shock. During the destruction of Chios alone, the Ottoman customs office recorded the export of about 45,000 slaves (GdL 13/9/22). Many slaves were captured at the fall of Messolonghi (Greek mainland), and others during the Egyptian campaign in the Peloponnese and on other occasions. In addition, Greek sailors who were forced to serve in the Ottoman fleet were practically slaves, an event in the Revolution remaining unnoticed by academic historiography.

The June 10, 1826 issue of the French newspaper La Quotidienne, with a full report from Messolonghi and a reference to the siege.

Immediately after the first news on the Revolution, some columnists pointed out that all Greeks are essentially slaves of the Turks, and that according to the then principles of law, slavery is a state of war.[42] Compassion for the victims of slavery fueled the philhellenic sentiments of the people and put pressure on governments to intervene. In the British Parliament, the opposition was questioning whether the government knew that “the markets of Smyrna and Constantinople are full of Greek women offered to the appetites of barbaric Muslims” (GdL 9 and 30/7/1822). Many philanthropic fundraising events were taking place, and many wealthy Europeans donated large sums of money to ransom Greek slaves, whose prices went up because of high demand. In Russia, too, Greek slavery stimulated a new wave of humanitarian mobilization. On the initiative of three Orthodox bishops, money was raised in order to ransom Greek slaves, with the estimate that about 5 rubles would be needed for each captive. Donations, even in church utensils, were offered by all social classes, all Christian ethnicities of Russia, even from remote areas of Siberia.[43] The slave trade was one of the aspects of the Peloponnesian genocide[44] which later provoked the humanitarian intervention of the Great Powers in Navarino. This theme is emphatically depicted in philhellenic art even after the middle of the 19th century. Surprisingly, nowadays, the Greek public knows very little about the Greek slavery, although this was a most dramatic event of the Revolution.

News excerpts from the philhellenic action of various “Greek Committees” in the USA. Top: A 12-year-old boy donates his watch to the Pittsburgh Philhellenic committee, requesting that the proceeds may be sent to the starving Greeks (Freedom’s Journal).

As the winter of 1822 entered 1823 without the defeat of the Revolution, the conditions were ripe for a change of policy by the Great Powers. Nobody could rule out the possibility that the threatened Russian invasion could take place in the spring of 1823, in which case it would not find much opposition from the public opinion of Europe. At the Verona Summit (completed in December 1822) which brought together the monarchs of Europe, the Greek issue was discussed very little, and no favorable decision was taken. Subsequently, however, after George Canning took over as foreign minister, Britain unilaterally changed policy in the spring of 1823, recognizing the Greeks as belligerents, while until then it considered them illegal rebels against a legitimate government. The status of belligerent was actually gained by the Greeks, as they managed to fulfill some commonly accepted criteria: protracted armed conflict, control of a large territory, existence of a responsible head authority.[45] This development gave some rights to the Greeks under international law, including the right to execute maritime interceptions and port blockades. It was the first step that would lead to the recognition of the interim government of Greece. The next step was the authorization of the loans in 1824 and 1825, proverbially famous in Greece till today as “the English loans”. These are usually characterized as a “rip-off”, but according to a recent technical analysis, taking into account the practices of the time, they were in fact favorable and essentially a philhellenic act.[46] It is true that the loaned money was mismanaged by the Greeks, but the initial terms were the best possible, and the granting of the loans was in effect the first act of recognition of a Greek state. This was also strongly reported by the European press, which closely monitored the Greek bond interest rates in the City, in relation to the political and military developments. For example, when it was announced that Admiral Cochrane (a naval legend of the time) was going to Greece to take command of the Greek fleet, interest rates fell by 15%.

Luck also played its role when the British Foreign Secretary Castlereagh committed suicide in August 1822 and was replaced by Canning, who was a friend and admirer of Lord Byron (They had served together in the House of Lords), and had a discreet sympathy for the Greeks and the Revolution. He also made the political calculation that a new state, which Britain could place under her influence, was about to be created. He did not immediately proceed with spectacular diplomatic initiatives, but in 1825, he proposed to the Porte the creation of a semi-autonomous Greek territory. His proposal was not only rejected, but at the same time the Egyptian campaign began, which attempted to colonize Peloponnese with Egyptians and transport the entire native population to the eastern slave markets. This was something that neither Canning, nor the Russians, nor other Europeans could tolerate. Canning’s cousin, Stratford, an ambassador in Constantinople, informed his minister that the Egyptians were enslaving the Greeks and converting the children to Islam. The idea of a military intervention for humanitarian reasons, for which public opinion had been prepared by the newspapers, began to be seriously discussed between the Great Powers, as we have seen. At the end of 1825 Russia also seemed ready to intervene unilaterally, which accelerated the decisions in London. In April 1826 Russia and Britain again proposed the creation of a semi-independent Greek state to the sultan, and this time Russia stated that in case of rejection she would intervene on her own. Almost at the same time, the news of the fall of Messolonghi (April 1826) and the death of the famous Lord Byron reached Europe. This caused new manifestations of Philhellenism with the participation of leading writers, painters (again Delacroix), musicians (like Rossini) and other personalities. Around that period the word “Philhellene” began to be used widely, firstly in France. The pressure on European governments was such that the pro-Egyptian policy of some circles in France was overcome. Luckily again for the Greeks, Canning became prime minister, replacing the seriously ill Liverpool in mid-1827. The Great Powers finally agreed to the Treaty of London in July 1827, after long discussions that lasted a few months (at that time it could take a month for a letter to be sent from London to St. Petersburg and the answer to come back). The Treaty was the first in the world to explicitly state the feasibility of a military operation “by sentiments of humanity.”[47] The admirals of the three Powers were ordered to impose the conditions of the Treaty on the Egyptians and the Turks. The operational instructions given to them were unclear (at least the written ones), but it seems that the green light was unofficially given for an intervention in favor of the Greeks, or at least this was not prohibited. The military intervention was sure to happen when the European officers and sailors, after some years of philhellenic galvanization, arrived in the Peloponnese and saw with their own eyes miserable condition of the Greeks who were on the verge of extinction. In mid-October 1827, officers who landed in the Peloponnese for reconnaissance informed Admiral Codrington that the Egyptians were burning villages, cutting down trees, destroying crops, and that the local population was in danger of starving to death. The inevitable naval battle happened in the port of Navarino (Peloponnese), and led to the destruction of the Egyptian –Turkish navy.

Gazette de France, March 10, 1827. “George Canning sent a new official memorandum to the sultan for the pacification in Greece. He called for an immediate end to hostilities on land and at sea and for a diplomatic solution to the Greek issue. It seems that Britain and Russia would do anything to stop the war.” SHP Collection.

The news of the naval battle was received with enthusiasm by the populace of Europe and the United States, but with mixed or even negative feelings by governments, due to concerns about the change of the status quo and the new role that Russia could play in the region. Most newspapers were satisfied. The philhellenic Morning Chronicle wrote that the victory was the justification of a philhellenic policy that Britain should have followed from the beginning of the Revolution.[48] It was not exactly the end of the war, but was the beginning of the end, since the Gordian Knot of military intervention had been broken. France then took the opportunity to act again as a Great Power, waging war against Ibrahim in the Peloponnese. While Western governments remained undecided about Greece’s future, in June 1828, Russia declared war on the Ottomans which ended with the Treaty of Adrianople (Edirne, 14/9/1829), where the Ottomans were forced to put the first signature for the independence of Greece.

In the dominant popular narratives about the intervention of the Great Powers and Greek independence, the simplistic picture of a tripartite scheme prevails: Hellenism was an isolated small entity, the Ottoman Empire was a large and powerful state, and the Christian Great Powers were a third party which intervened due to Philhellenism and geopolitical interests. This is also the view of nationalist Turkish historians, who believe that in Navarino “the victory ‘was snatched out’ of their hands“.[49] In their narrative, Egypt appears as a member of the Empire, and foreigners intervene in their “internal affairs”. I think that this analysis cannot stand the factual test. The concept of two worlds in conflict is a more useful analytical tool, with the Greeks being an integral part of the geopolitical entity of Europe (which includes Russia), while Egypt, North Africa, various semi-autonomous pashaliks and the main body of the Ottoman Empire were parts of a Middle Eastern Islamic entity, but not one state. It is true that there has never been a strong European collective identity anyhow close to the concept of a “European nation”, let alone one that would include the Greeks and other Eastern Orthodox peoples. But the same applies to the Ottomans, even if we only consider the Muslims of the Empire. There was, however, a loose unity of ethnicities on each of the two sides, based mainly on common religions, linguistic affinities, common alphabets, and historical references. This two-worlds model can be verified by demographic and other criteria, but I consider it self-evident and it is more or less observable even today. The two worlds had clashed militarily in the past, with the most important multinational battles being in Kosovo (14th century), Vienna (1683) and Lepanto (1571). At the age of the Revolution the conflict had taken on a strong economic character, as the Ottoman Empire was forced to accept a series of economic and political concessions to the western states. The Greek Revolution was a shock that motivated the Empire to a series of semi-failed attempts at modernization, which continued until its dissolution, as it was not possible to bridge its internal divisions. On the other hand, the West had its own internal divisions and rivalries, a factor that extended the Empire’s life until WW 1.

In the above-mentioned unifying elements that compose the entity of a “wider Europe”, the legacies of classical and medieval Greece are omnipresent. In Western Europe at the time of the Revolution, classical values fueled, among other things, the radical and liberal political movements. These are commonly said to originate in the era of the French Revolution or the Enlightenment, when a renewed interest in classical Greek philosophy appeared. Modern scholars of the Enlightenment tend to surpass the established historiography that presents this period as a turning point and as the beginning of a new epistemological and political paradigm. Revisionists challenge the Enlightenment as the starting point of “modernity,” and argue that it was rather a period of smooth transition. It is believed that the preoccupation with antiquity at the time was not a choice made by some intellectuals for special reasons, but that “the ancient world was a ubiquitous presence that imposed itself as dominant filter through which educated Europeans constructed as well as viewed reality, as they had done since the Renaissance. Indeed, antiquity was an inescapable […] background to the intellectual background of the age. “[50] For the revisionists, “Enlightenment” (often put in quotation marks) is considered a Franco-centric version of history, or a term that is gradually losing its meaning.[51] But even these modern analyses of the Enlightenment remain “West-centric”, as they focus only on Western Europe.

In the Hellenic cosmos, the continuity with classical antiquity was more of a living social experience, due to the traditions and the Greek language (vernacular and ecclesiastical) which had even expanded “ecumenically” in the Balkans.[52] The contact with classical antiquity did not cease during the Byzantine and post-Byzantine period, and “Byzantium was the guarantor of the historical flow of the Greek world.“[53] Suffice it to say that 95% of the classic Greek texts we know and read today come from Byzantine manuscripts later than the 9th century, which were constantly reproduced by Greek-speaking Byzantine writers for Greek-speaking readers.[54] Even when typography flourished in the rest of Europe, in the Turkish-occupied areas of Hellenism monks continued to copy classical texts by hand, struggling to maintain as much learning as they could under the circumstances. Since the 11th century, the Russians have grasped the thread of continuity with regards to Greco-Byzantine culture, adopting the alphabet, the Orthodox religion and religious art, and later the classical education.

Indicative of the organic relation of Philhellenism and European civilization is the fact that distinguished figures of the philhellenic movement were also active in the political and social movements of their countries. These relationships are more than evident in emblematic works, such as Percy Shelley’s poem “Hellas” (in which he writes “we are all Greeks“) based on the Aeschylus’ Persians, an allegory to the struggle between freedom and tyranny.[55] There are many other less known connections, evident though in personal stories, such as Byron and Shelley’s circle of friends which included the pioneering feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, the anarchist philosopher William Godwin and the utopian socialist Robert Owen.[56] Another philhellenic circle that remains relatively unknown in Greece was that of the Irish and Scottish radicals and patriots. Even the most famous of them, the Irishman Richard Church, is often referred to as an “Englishman”. They had a special relationship with the struggling Greeks, because they found an analogy with the situation in their homelands that were under English rule.[57] Many Irish and Scots took part in the Philhellenic Greek Committee of London, where the main “credential” for participation was nationalism and opposition to the government, to the extent that the Commission was described as a “protest movement” by historian David Brewer.[58] In fact, R. Church, and apparently other Britons whose names we do not know, financially supported the Fraternal Society long before 1821.[59] The Irish Philhellene Sir Edward Lowe, although he did not fight for the Revolution, came to love Greece while serving in the Ionian Islands, where he was a comrade-in-arms of R. Church and Kolokotronis, and instructor of Greek battalions. Later, as commander on the island of Saint Helena (1816-1821), he was responsible for guarding Napoleon, but also pioneered the emancipation of the slaves of the island. Prisoner Napoleon (from whom the Greeks had hoped to get assistance before the Revolution) appreciated Lowe because “perhaps they exchanged some cannon-balls” in the Napoleonic wars. One unsung Philhellene, Gilbert Lafayette, was the hero of the two Revolutions (the French and the American). He could not act openly because he had previously been associated with Carbonarism, but he influenced the Greek Committee of Paris through the members of his family who participated, and through his alter ego Guillaume-Mathieu Dumas.[60]

I have outlined some of the less celebrated aspects of the 1821–’29 Philhellenism movement, arguing that this phenomenon was the manifestation of a fundamental – although not strong and solid – European unity and European culture. The latter had inherited from classical antiquity the values of freedom and the concepts of natural law and human rights.[61] Ironically, the same values were responsible for the fragmentation of Europe into nations, religious dogmas and political factions.

Further from Europe, there may have been non-Eurocentric perceptions of the Revolution, at a time when there was already a globalization in terms of the dissemination of news and ideas. I conclude this present article with an interesting trans-national case, namely the impact that the Revolution had on the first newspaper of emancipated Black Americans, the Freedom’s Journal, published since March 1827 in New York. The newspaper, interested mainly in the anti-slavery movement, saw in the Greek Revolution a struggle of slaves against oppressive masters, and gave the news from Greece an importance comparable to the news from Haiti, Africa and the West Indies. Among others, on 21/12/1827 it published with great satisfaction the news on the Naval Battle of Navarino. Interestingly, it also expressed sympathy for the Ottoman janissaries and the women of the harems, the former in fact slaughtered by the “tyrant” sultan Mahmut II a year earlier,[62] whom it considered (not without some justification) to be slaves. Below are few verses from philhellenic poems published in the Freedom’s Journal, where allusions are included to the motto, “liberty or death” and the universal symbols of oppression, chains:

TO GREECE (F.J. 12/10/1827)

Hail! Land of Leonidas still,

Though Moslems encircle thy shore; […]

Yet quail not, descendants of those,

The heroes of Marathon’s plain;

Better lay where you fathers repose,

Than wear the fierce Ottoman’s chain. […]

GREEK SONG (F.J. 7/9/1827)

Mount, soldier, mount, the gallant steed,

Seek, seek, the ranks of war.

‘Tis better there in death to bleed,

Than drag a tyrant’s car.

Strike! Strike! Nor think the blow unseen

That frees the limbs where chains have been.

THE SONG OF THE JANISSARY (F.J., 4/5/1827)

For a time – for a time may the tyrant prevail,

But himself and his Pachas before us shall quail;

The fate that torn Selim in blood from the throne,

We have sworn haughty Mahmoud! Shall yet be thy own.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(Dates in DD/MM/YYYY. Transliteration of Greek names and translation of Greek titles is added to the original citation.)

- Barau Denys. “La mobilisation des philhellènes en faveur de la Grèce, 1821-1829”, in: Cambrézy Luc, Véronique Lassailly-Jacob (eds.) Populations réfugiées: De l’exil au retour [online]. Marseille: IRD Éditions, 2001. https://books.google.gr/ and http://books.openedition.org/irdeditions/6650

- Brewer David , The Greek War of Independence, Abrams, 2011, ch. 14. http://books.google.gr

- Comerford Patrick, “Sir Richard Church and the Irish Philhellenes in the Greek War of Independence”, in John Victor Luce et al. (eds.) The Lure of Greece: Irish Involvement in Greek Culture, Literature, History and Politics, εκδ. Hinds, 2007, ch. 1. In www.hinds.ie/samplePages/52273b8f54149.pdf

- Craig Calhoun, The Roots of Radicalism: Tradition, The Public Sphere, and Early Nineteenth-Century Social Movements, University of Chicago Press, 2012, http://books.google.gr

- Crawley C. W., The Question of Greek Independence, Cambridge University Press, 2014, pp. 22, 23, 30, 31. http://books.google.gr

- Dieli Marta, “The Enlightenment and the Teaching of Ancient Greek Grammar in Greece”, in Loughlin F. and Johnston A. (eds.) Antiquity and Enlightenment Culture, Brill, 2020, pp 173–192. https://brill.com

- Dimakis Jean, La guerre de l’ independence Grecque vue par la presse française, …, Paris, 1974.

- Dimakis Jean, “La presse de Vienne et la question d’orient: 1821-1827”. Balkan Studies, ΙΜΧΑ, 16, (1975), pp. 35-43.

- Dimakis Jean, «Το πρόβλημα των ειδήσεων περί της Ελληνικής Επαναστάσεως εις τον Γαλλικόν τύπον», Ελληνικά, 19 (1966), pp. 54-91. (The question of the news on the Greek Revolution in the French press)

- Dimopoulos Aristide G., L’opinion publique Francaise et la revolution Grecque, Nancy, 1962.

- Edelstein Dan, interview to Alex Shashkevich, “Stanford scholar examines the roots of human rights” about the book Edelstein D., On the Spirit of Rights [University of Chicago Press, 2018], 4/1/2019, https://news.stanford.edu/2019/01/04/roots-human-rights/

- Epictetus, Dissertations, in Theophrasti Characteres Graece et Latine, Ambrosio Firmin Didot, Paris 1840. http://books.google.

- Erdem Güven, “The Image and the Perception of the Turk in Freedom’s Journal”, Journalism History, (2016) 41:4, pp. 191-199, www.academia.edu

- Gell William, Narrative of a Journey in the Morea, London, 1823. http://books.google.gr.

- Ghervas Stella, “Le philhellénisme d’inspiration conservatrice en Europe et en Russie”, in Peuples, etats et nations dans le Sud-Est de l’Europe, Bucarest, 2004. www.academia.edu.

- Heraclides Alexis and Ada Dialla, Humanitarian Intervention in the Long Nineteenth Century, Manchester University Press, 2015. JSTOR.

- Jelavich Barbara, Russia’s Balkan Entanglements, 1806-1914, Cambridge University Press, Mar 11, 2004 [1993], pp 49-76.

- Kaldellis Anthony, Hellenism in Byzantium. The Transformations of Greek Identity and the Reception of the Classical Tradition. Cambridge University Press. 2008.

- Klausing, Kyle J., “We Are All Greeks: Sympathy and Proximity in Shelley‘s Hellas”, Scholarly Horizons: University of Minnesota, Morris Undergraduate Journal: (2015) Vol. 2: 2, Art. 3. http://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu

- Konstantinou Evangelos, “Graecomania and Philhellenism”, in European History Online (EGO), έκδοση Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG), Mainz 23-11-2012. http://www.ieg-ego.eu/konstantinoue-2012-en

- Loosemore Jo, Sailing against slavery, 2008, www.bbc.co.uk

- Loughlin F. & Johnston A., Antiquity and Enlightenment Culture, Brill, 2020. http://books.google.gr

- Loukides George (ή Γ. Λουκίδης), Δύο ομιλίες του Π. Πατρών Γερμανού στην Αγ. Λαύρα το Μάρτιο 1821, www.cademia.edu. 2019. (Two speeches by P. Patron Germanos in Ag. Lavra in March 1821)

- Lucien J. Frary, Russian consuls and the Greek war of independence (1821–31), Mediterranean Historical Review, (2013) 28:1, 46-65, www.tandfonline.com/

- Maioli, Roger. Review of The Specter of Skepticism in the Age of Enlightenment, by Anton M. Matytsin. The Scriblerian and the Kit-Cats, vol. 51 no. 2, (2019), pp. 158-160. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/scb.2019.0065.

- Malatras Christos, “The making of an ethnic group: the Romaioi in 12th-13th century”, in Ταυτότητες στον ελληνικό κόσμο (από το 1204 έως σήμερα), Δ’ Ευρωπ. Συνέδριο Νεοελλ. Σπουδών, Γρανάδα, 9-12 Σεπ. 2010, επιμ. Κων. Α. Δημάδης.

- Maltézou Chryssa, «Η διαμόρφωση της ελληνικής ταυτότητας στη λατινοκρατούμενη Ελλάδα», Études balkaniques, 1999, 6, pp. 103-119 (The formation of the greek identity in the latin-occupied Greece).

- Morris, Ian Macgregor, ‘To Make a New Thermopylae’: Hellenism, Greek Liberation, and the Battle of Thermopylae. Greece & Rome, 2000, vol. 47, 2, pp. 211–230. JSTOR.

- Nestor-Iskender, The Tale of Constantinople, http://myriobiblion.byzantion.ru/romania-rosia/nestor2.htm.

- Penn Virginia, “Philhellenism in Europe, 1821-1828”. The Slavonic and East European Review, 1938, 16(48), 638–653. www.jstor.org

- Prousis Theophilus C., “Russian Philorthodox Relief During The Greek War Of Independence”, University of North Florida, History Faculty Publications, (1985), 17, pp. 31-62. http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ahis_facpub/17

- Prousis, Theophilus C., “British Embassy Reports on the Greek Uprising in 1821-1822: War of Independence or War of Religion?”, University of North Florida, History Faculty Publications, 2011. http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ahis_facpub/21

- Quack-Μανουσάκη Ρεγγίνα, «Ελληνική Επανάστασις: Η πολιτική του Metternich και η κοινή γνώμη στη Γερμανία». Πελοποννησιακά, Δ’ (1996-97) [1995], pp. 329-338. (Quack-Manousaki Regina, “Greek Revolution: Metternich’s Politics and Public Opinion in Germany”).

- Swatek-Evenstein Mark, A History of Humanitarian Intervention, Cambridge University Press, 2020, http://books.google.gr

- Tabaki-Iona Frédérique, “Philhellénisme religieux et mobilisation des Français pendant la révolution grecque de 1821-1827”, Mots. Les langages du politique, 79 / 2005, http://journals.openedition.org/mots/1348.

- Tachiaos Anthony-Emil N. “The national regeneration of the Greeks as seen by the Russian intelligentsia”, Balkan Studies, v. 30, n. 2, pp. 291-310, 1989. https://ojs.lib.uom.gr/index.php/BalkanStudies/article/view/2211

- Αποστολίδης Νίκος & Βελέντζας Κωνσταντίνος, «Ήταν ληστρικά τα δάνεια που λάβαμε από την Αγγλία;», Καθημερινή, 31-3-2020. www.kathimerini.gr/

- Αργυράκος Γεώργιος & Αργυράκου Κωνσταντίνα-Κορασόν, Η Επανάσταση του ’21 στην Gazette de Lausanne. Ανασκόπηση – Περίληψη των ειδήσεων (Απρίλιος 1821 – Φεβρουάριος 1823). Ελίκρανον, Αθήνα, 2017.

- Αργυρίου Αστέριος, Les exégeses grecques de l‘ Apocalypse a l‘epoque turque (1453-1821), Εταιρεία Μακεδ. Σπουδών, Θεσσαλονίκη, 1982. http://thesis.ekt.gr/

- Αρς Γκριγκόρι (1925-2017), short biography, www.dardanosnet.gr/

- Δημάκης Ιωάννης, see Dimakis Jean.

- Ευθυμιάδης Απόστολος, «Προσφορά αίματος και θυσιών της Θράκης 1361 – 1829», 1971. http://ainites.gr/wp-content (Euthimiadis Apostolos, Offerings of blood and sacrifices by Thrake, 1361-1829)

- Ιωαννίδου – Μπιτσιάδου Γεωργία, Η ρωσική διπλωματία στη δεύτερη φάση της Ελληνικής Επαναστάσεως (από τα τέλη του 1825 μέχρι το 1830), Βαλκανικά Σύμμεικτα, 1989, 3, p 62. https://ojs.lib.uom.gr (Ioannidou – Bitsiadou Georgia, “Russian diplomacy in the second phase of the Greek Revolution”).

- Καραθανάσης Αθανάσιος Ε. «Γύρω από το γερμανικό φιλελληνισμό. Μαρτυρίες και δοκουμέντα της περιόδου 1821-23». Βαλκανικά Σύμμεικτα, (1981) τομ. Α’, 45-60. (Karathanasis Athanasios E. “On German philhellenism. Testimonies and documents of the 1821-23 period.”)

- Κατσιαρδή-Hering Όλγα, «Από τις εξεγέρσεις στις επαναστάσεις των χριστιανών υποτελών της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας στη Νοτιοανατολική Ευρώπη (περ. 1530-1821). Μια απόπειρα τυπολογίας», In: Τα Βαλκάνια, Εκσυγχρονισμός, ταυτότητες, ιδέες, Συλλογή κειμένων προς τιμήν της καθ. Ν.Ντάνοβα, Heraklion, Crete, 2014, 575-618. Academia.edu. (Katsiardi-Hering Olga, “From the uprisings to the revolutions of the Christian subjects of the Ottoman Empire (approx. 1530-1821)).

- Κοντογιώργης Γιώργος, τηλεοπτική ιστορική σειρά «’21. Η Αναγέννηση των Ελλήνων», κανάλι MEGA, 18/19 Απρ. 2019, περίπου 6ο λεπτό. www.megatv.com/21/default.asp?catid=43549 (Kontogiorgis George, historical TV series «’21. The Renaissance of the Greeks “, MEGA channel, Apr. 18/19, 2020, approx. at the 6th minute).

- Κρεμμυδάς Βασίλης, Η Ελληνική Επανάσταση του 1821, Αθήνα, Gutenberg, 2006. (Kremmydas V., The Greek Revolution of 1821).

- Λούβη-Κίζη Ασπασία, «Η εκπαίδευση στο Βυζάντιο», Αρχαιολογία, (1987), τχ. 25, p 26-30. https://www.archaiologia.gr/ (Louvi-Kizi Aspasia, “Education in Byzantium”).

- Λούκος Χρήστος, review of Theophilus C. Prousis (1994) Russian Society and the Greek Revolution. Μνήμων, (1998) 20, pp. 337-340. (Loukos Christos, review of Theophilus C. Prousis, 1994).

- Λουλές Δημήτρης, «Η Ελληνική Επανάσταση και ο βρετανικός τύπος …», Δωδώνη, 12 (1983), pp. 99-138. (Loules Dimitris, “The Greek Revolution and the British Press”).

- Λουλές Δημήτρης, Ο ρόλος της Ρωσίας στη διαμόρφωση του Ελληνικού Κράτους, Αθήνα 1981. (Loules D., The role of Russia in shaping the Greek State).

- Λουλές Δημήτρης, «Ο Βρετανικός τύπος για τη ναυμαχία του Ναβαρίνου», Μνήμων, 7 (1979), pp. 1-11. https://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/ (Loules D., “The British Press on the Naval Battle of Navarino”).

- Μαλατράς Χρήστος, «H Ελληνικότητα του Βυζαντίου στη μεταπολεμική ιστοριογραφία», Ιστορικά Θέματα, 104, (2011), 25-37. (Malatras Christos, “The Greekness of Byzantium in the post-War historiography”).

- Παπαγεώργιος Σπυρίδων, «Του Μητροπολίτου Άρτης Ιγνατίου Α’ Αλληλογραφία», Επετηρίς, Φιλολογ. Σύλλ. Παρνασσός, 1917, pp. 207, 208. (Papageorgios Spyridon, “Correspondence of the Metropolitan of Arta Ignatius I”).

- Παπουλίδης Κωνσταντίνος Κ., Η Ρωσία και η Ελληνική Επανάσταση τού 1821-1822. 1983, https://ojs.lib.uom.gr (Papoulidis K., Russia and the Greek Revolution).

- Σιμόπουλος Κυριάκος, Πώς είδαν οι ξένοι την Ελλάδα του ‘21, Πολιτιστικές Εκδόσεις, Αθήνα, 2004. (Simopoulos Kyriakos, How foreigners saw the Greece of the 1821 Revolution).

- Στείρης Γεώργιος, Οι απαρχές της νεοελληνικής ταυτότητας στο ύστερο Βυζάντιο, 2017. http://indeepanalysis.gr. (Steiris Georgios, The beginnings of the new Hellenic identity in the Late Byzantium).

- Τσελίκας Αγαμέμνων, personal communication (email), Apr. 13, 2020 (Tselikas Agamemnon).

- Φραντζής (ή Σφραντζής) Γεώργιος, Χρονικό Majus, Νέα Ελληνική Λογοτεχνία (Α’ Λυκείου) – Βιβλίο Μαθητή (Εμπλουτισμένο), ebooks.edu.gr. (Frantzis (or Sfrantzis) Georgios, Chronicon Majus, ch. B ‘. Modern Greek Literature, textbook).

Newspapers

- Algemeine Preussische Staat Zeitung, 1821, https://digi.bib.uni-mannheim.de/

- Freedom’s Journal, at: Wisconsin Historical Society, www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS4415

- Galignani’s Messenger, 1821. https://books.google.gr/

- Gazette de Lausanne, www.letempsarchives.ch/

- Gentleman’s Magazine, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006056643.

- Moskovskiye Vedomosti (Moscow News), Jul.-Dec.1821, https://books.google.cz/

[1] “The beginning of learning is the investigation of the terms”. A quotation attributed to Antisthenes and Socrates (αρχή παιδεύσεως η των ονομάτων επίσκεψις) in various forms. Epictetus, Dissertations, A’, 17, 12, in Theophrasti Characteres Graece et Latine, Ambrosio Firmin Didot, Paris 1840, p. 58.

[2] Many historians believe that the roots of modern Greek national consciousness can be found in the 13th century, caused by the conflicts with the Franks and others. See e.g. Maltézou Chryssa, «Η διαμόρφωση της ελληνικής ταυτότητας στη λατινοκρατούμενη Ελλάδα», Études balkaniques, 1999, 6, pp. 103-119. Also, Kaldellis A. (2008). Others date this evolution to the Late Byzantine era, e.g. Στείρης Γεώργιος, «Οι απαρχές της νεοελληνικής ταυτότητας στο ύστερο Βυζάντιο», 2017.

[3]For a summary of the various views until 2011, see Μαλατράς Χρήστος, «H Ελληνικότητα του Βυζαντίου στη μεταπολεμική ιστοριογραφία», Ιστορικά Θέματα, 104, Ιούλ. 2011, 25-37. For an overview of the position of Hellenism in Byzantium see Kaldellis Anthony, Hellenism in Byzantium. The Transformations of Greek Identity and the Reception of the Classical Tradition, 2008. ● Λούβη-Κίζη Ασπασία, «Η εκπαίδευση στο Βυζάντιο», Αρχαιολογία, 1987, 25, σ. 26-30. ● Malatras Chr., “The making of an ethnic group: the Romaioi in the 12th-13th century”, 2010.

[4] Crawley CW, The Question of Greek Independence, 2014, pp. 22, 23, 30, 31.

[5] Παπουλίδης Κωνσταντίνος Κ., Η Ρωσία και η Ελληνική Επανάσταση …, 1983.

[6] Ιωαννίδου – Μπιτσιάδου Γεωργία, «Η ρωσική διπλωματία στη δεύτερη φάση της Ελληνικής Επαναστάσεως …», Βαλκανικά Σύμμεικτα, 1989, 3, p. 62. ● Lucien J. Frary, Russian consuls and the Greek war of independence…, Mediter. Historical Review, (2013), 28: 1, 46-65.

[7]Λούκος Χρήστος, review of Theophilus C. Prousis (1994) Russian Society and the Greek Revolution. Μνήμων, (1998) 20, pp. 337-340.

[8] A summary of the uprisings, attempted uprisings or revolutions of the Balkan Christians from the 16th to the 21st century is in Όλγα Κατσιαρδή-Hering, «Από τις εξεγέρσεις στις επαναστάσεις των χριστιανών υποτελών της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας …», 2014, p. 587- 603.

[9] Tachiaos Anthony-Emil, “The national regeneration of the Greeks as seen by the Russian intelligentsia”, Balkan Studies, v. 30, n. 2, p. 294-296, 1989. https://ojs.lib.uom.gr/

[10] Argyriou Asterios, Les exégeses grecques de l ‘Apocalypse a l’epoque turque (1453-1821), 1982, pp. 22-25.

[11] Ghervas Stella, “Le philhellénisme d’inspiration conservatrice en Europe et en Russie”, 2004, p.105, 106.

[12] Ars Grigori (1925-2017), short biography, www.dardanosnet.gr/

[13] Λουλές Δ., Ο ρόλος της Ρωσίας στη διαμόρφωση του Ελληνικού Κράτους. Αθήνα 1981.

[14] References to relevant studies, many in Russian, until 1983, exist in Παπουλίδης Κ., Η Ρωσία και η Ελληνική Επανάσταση, 1983.

[15] Jelavich Barbara, Russia’s Balkan Entanglements, 1806-1914, CUP, Mar 11, 2004 [1993] pp. 49-76.

[16] Prousis Theophilus, Russian Philorthodox Relief During The Greek War Of Independence, 1985.

[17]The number of newspapers published in Russia was clearly smaller than in Western Europe, and all were subject to state censorship. As I don’t know the Russian language, I only have a faint picture of the relevant news. I note that the Moskovskiye Vedomosti (Moscow News), which is digitized online, had extensive news of the Revolution on each of its issues (2 in a week) in the second half of 1821.

[18]From the book Αργυράκος Γ. & Αργυράκου Κ.Κ., Η Επανάσταση του ’21 στην Gazette de Lausanne. … (Απρ. 1821 – Φεβρ. 1823). Ελίκρανον, Αθήνα, 2017.

[19]Then the news from the East Europe and Greece were reaching W. Europe with a delay of about a month. At the same time, the New (Gregorian) Calendar was 12 days ahead of the Old (Julian) Greek and Russian calendar.

[20]Φραντζής (ή Σφραντζής) Γεώργιος, Χρονικό, Chronicon Majus, ch. B ‘. Νέα Ελληνική Λογοτεχνία, ebooks.edu.gr

[21]Nestor-Iskender, The Tale of Constantinople. It was written soon after the Fall of Constantinople, by an author believed to be a monk living inside the city, although he claims that he was a Cryptochristian fighting with the Turkish army. According to this chronicle, Emperor Constantine declares that he is ready to die for his motherland (отечество) (par. S. 244). He also summons his men to fight till death for the Orthodox faith (за православную веру) (S. 231, 251, 259) and for the churches (S. 251, passim). In the same text, we can find a paraphrase of another standard slogan of the Revolution, “liberty or death” (S. 241). The chronicle includes the first attestation of the prophecy about the “blond nation” which will liberate Constantinople. In Russian, the “blond nation” etymologically, semantically and phonetically points to the Russian nation. The chronicle in old and new Russian is available at http://myriobiblion.byzantion.ru/romania-rosia/nestor2.htm.

[22] Αργυράκος Γ. & Αργυράκου KK, 2017, p. 36, fn 7. The “neoteric” historiographic school analyzes only the word “Motherland” (πατρίδα), attributing it to the French Revolution, and has no comments for the word “Faith” (πίστις). See, e.g. Κρεμμυδάς Β., Η Ελληνική Επανάσταση του 1821), 2006, p. 63.

[23]Morris, Ian Macgregor, ‘To Make a New Thermopylae’: Hellenism, Greek Liberation, and the Battle of Thermopylae. Greece & Rome, (2000), vol. 47, 2,pp. 211–230. JSTOR.

[24]Detailed information on the news about bishop Germanos is available at Loukides George, «Δύο ομιλίες του Π. Πατρών Γερμανού στην Αγ. Λαύρα το Μάρτιο 1821», 2019. www.academia.edu.

[25]These are not exaggerations. The army was often sending to the capital such grisly proofs of their “successes”.

[26]Prousis Th. C., “British Embassy Reports on the Greek Uprising in 1821-1822: War of Independence or War of Religion?”. Univ. N. Florida, History Faculty Publications, 2011.

[27]For the christian dimension of French Philhellenism, see Tabaki-Iona Frédérique, “Religious Philhellenism and mobilization in France during the 1821–1827 Greek Revolution”, Mots. Les langages du politique, 79, 2005.

[28] Algemeine Preussische Staat Zeitung, June 7 & 12, 1821. https://digi.bib.uni-mannheim.de/

[29]Penn Virginia (1938). “Philhellenism in Europe, 1821-1828”. The Slavonic and East Eur. Review, 16 (48), 638–653.

[30] Quack-Μανουσάκη Ρεγγίνα, «Ελληνική Επανάστασις: Η πολιτική του Metternich και η κοινή γνώμη στη Γερμανία». Πελοποννησιακά, 4 (1996-97) [1995], 329-338. ● Καραθανάσης Αθανάσιος Ε. «Γύρω από το γερμανικό φιλελληνισμό». Βαλκανικά Σύμμεικτα, (1981) vol. Α’, 45-60.

[31] Penn V. (1938), p. 649.

[32]Konstantinou Evangelos, “Graecomania and Philhellenism”, in: European History Online (EGO), Mainz 2012-11-23.

[33] Non-exhaustive bibliography: Dimakis Jean (a) La guerre de l’independence Grecque vue par la presse française,…, Paris, 1974. (b) La presse de Vienne et la question d.’ Orient: 1821-1827. Balkan Studies, IMXA, 16, (1975), pp. 35-43. (c) Το πρόβλημα των ειδήσεων περί της Ελληνικής Επαναστάσεως εις τον Γαλλικόν τύπον, Ελληνικά, 19 (1966), pp. 54-91. ● Dimopoulos Aristide G., L’opinion publique Francaise et la revolution Grecque, Nancy, 1962. ● Λουλές Δημ., «Η Ελληνική Επανάσταση και ο βρετανικός τύπος …», Δωδώνη, 12 (1983), pp. 99-138.

[34] Penn V. (1938), p. 645.

[35] Σιμόπουλος Κυριάκος, Πώς είδαν οι ξένοι την Ελλάδα του ’21, Α’, p. 399, Athens, 2004.

[36] Gell William, Narrative of a Journey in the Morea, London, 1823, pp. 13, 14. He also comments caustically on the Europeans’ habit of spitting on the floor or even on carpets, something that Greeks and Turks hated (pp. 11, 12).

[37]There are many references to memoirs and other writings of Philhellenes in the 5-volumes work of K. Simopoulos How foreigners saw the Greece of the 1821 Revolution. Several such memoirs etc are available online at books.google.gr, archive.org, etc.

[38] Gentleman’s Magazine, July to December 1821, vol. 91, part 2, p. 366.

[39]The fashion of decorating the big European cities by looting works of art from other countries, in modern times began in Napoleon’s Paris. London has been dragged into this fashion by the need to compete with Paris as a world art center.

[40]It probably referred to the persecutions and executions of Christians that took place in Philippoupolis (Plovdiv) in 1822. See Ευθυμιάδης Α., 1971, p. 14.

[41] Loosemore Jo, Sailing against slavery, 2008, www.bbc.co.uk.

[42]Article in the St. James’s Chronicle (London) re-published in the Galignani’s Messenger, Apr. 11, 1821. The G.M. was an English language paper published in Paris by the Italian journalist Giovanni Antonio Galignani.

[43] Prousis Theophilus, 1985, pp. 40-49.

[44] The term “genocide” was coined much later, in 1940s, but the Greeks were calling themselves “genos” since the Late Byzantine time.

[45] Heraclides Alexis & Ada Dialla, Humanitarian Intervention in the Long Nineteenth Century, Manchester Univ. Press, 2015, p. 106. JSTOR.

[46]Αποστολίδης Νίκος & Βελέντζας Κωνσταντίνος, «Ήταν ληστρικά τα δάνεια που λάβαμε από την Αγγλία;», Καθημερινή, 31-3-2020. www.kathimerini.gr

[47] Swatek-Evenstein Mark, A History of Humanitarian Intervention, 2020, p. 58.

[48] Λουλές Δ., “Ο Βρετανικός τύπος για τη ναυμαχία του Ναβαρίνου”, Μνήμων 7 (1979), pp. 1-11.

[49] Heraclides A. & Ada Dialla, Humanitarian Intervention…, p. 117.

[50] Loughlin F. & Johnston A., Antiquity and Enlightenment Culture, 2020, pp. 5, 6.

[51] Maioli, Roger. Review of The Specter of Skepticism in the Age of Enlightenment, by Anton M. Matytsin. The Scriblerian and the Kit-Cats, vol. 51 no. 2, (2019), pp. 158-160.

[52] Dieli M., “The Enlightenment and the Teaching of Ancient Greek Grammar…”, 2020, p. 174.

[53] Κοντογιώργης Γιώργος, historical TV series, «’21. Η Αναγέννηση των Ελλήνων», MEGA Channel, Apr. 18/19, 2019, approx.. at the 6th minute. www.megatv.com/21/default.asp?catid=43549

[54] Τσελίκας Αγαμέμνων, personal communication (email), Apr. 13, 2020.

[55]Klausing, Kyle J. (2015) “‘We Are All Greeks:’ Sympathy and Proximity in Shelley’s Hellas,” Scholarly Horizons: Univ. of Minnesota, Morris Undergraduate J. vol. 2: 2, art. 3, pp. 16, 17.

[56] Craig Calhoun, The Roots of Radicalism:…, 2012, p. 272.

[57] Comerford Patrick, “Sir Richard Church and the Irish Philhellenes in the Greek War of Independence”, 2007, ch. 1.

[58] Brewer David, The Greek War of Independence, Abrams, 2011, ch. 14. Books.google.gr

[59] See letter from Dimitrios Schinas to the Metropolitan of Arta, Ignatius I, January 1816. In: Παπαγεώργιος Σπυρίδων, «Του Μητροπολίτου Άρτης Ιγνατίου Α’ Αλληλογραφία», Επετηρίς, Φιλολογ. Σύλλ. Παρνασσός, 1917, pp. 207, 208.

[60]Barau Denys. “La mobilisation des philhellènes en faveur de la Grèce,…”, 2001, p. 48.

[61] Edelstein Dan, interview “Stanford scholar examines the roots of human rights”, Jan. 4, 2019, https://news.stanford.edu

[62] Freedom’s Journal, digitized, Wisconsin Society. www.wisconsinhistory.org/ ● Erdem Güven, “The Image and the Perception of the Turk in Freedom’s Journal”, Journalism History, (2016), 41: 4, pp. 191-199, academia.edu. The article also extends to historical issues not covered by its title, and clearly promotes a beautified image of the Ottoman Empire.