BY JIM SMYTH

ABSTRACT

In his book, The Philhellenes, C.M. Woodhouse comments:

“Again and again, it will be found in the story of the Philhellenes that they originated from the minority peoples of the British Isles” (p.64)

Yet he offers no more than a cursory explanation for this, and other writers on the topic tend to use the collective term “British” for all participants.

Given that this is formally accurate since English colonialism had long brought the so-called Celtic Fringe under its control – however challenged this control was in reality – it begs the question as to what motivated this group to engage with the Greek War of Independence as opposed to the minimalist involvement of the English themselves.

In raw numbers Irish participation was small, numbering about 40. However, among that number there were individuals who played an important part in a number of crucial areas: political, military, fund raising, journalistic and other literary activities. This would include participants such as Richard Church, Charles Napier, Rowan Hamilton, Edward Blaquiere, Thomas Moore and James Emerson[1].

THE COLONIAL INHERITANCE: GREECE AND IRELAND

The actual geographical possession of land is what empire is in the final analysis all about.

Although while Ireland and Greece do not share a common history, they were both subjected to domination for centuries: four in the Greek case and double that for Ireland. Said’s ‘final analysis’ is clearly correct, and it marks a starting point. Colonial domination takes many forms, and the enforced possession and exploitation of land differs from case to case. These differences structure both social and economic realities, as well as forms of resistance.

These different models of domination had important consequences for the emergence of social movements which were eventually to coalesce around a struggle for nationhood. Geography played a part: Ireland, an island floating on the edge of Europe, was insulated from the bloody struggles which consumed the continent for centuries starting with the decline of Roman rule. The affinity with a historical past -a central aspect of nationalist ideology- was fractured for Greek speakers by centuries of Roman occupation followed by the impact of Byzantine rule and after the final implosion of this Empire in 1453 to be followed by four centuries of Ottoman domination.[3] In contrast, it was not until the Anglo-Norman invasion of the 12th century that the very nature of Irish culture was challenged on the general grounds that the “mere Irish” were uncivilized barbarians[4]. To achieve the objective of seizing, occupying and making a claim to ownership, England saw no option of a compromise with the Irish-apart from a small minority they could coerce or bribe into submission.[5] One important consequence of this was the creation of a disaffected population that refused to accept the rule of a small clique- the “Ascendency” that had confiscated their land by force and regarded the masses as ‘a seething mass of barley repressed sedition.

The impact of the French Revolution had caused turmoil the length and breadth of Europe and as much in Ireland as anywhere else. Conflict in Ireland over the previous two centuries had scattered the Irish all across Europe as soldiers of fortune in the armies of Austria, Spain and, in particular France. Irish Colleges spread across the continent for the education of priests as well as displaced Irish and their sons. These connections ensured that ideas underpinning the revolution soon reached Irish shores. As in pre-revolutionary France, the creation of public opinion through the medium of newspapers, broadsheets and pamphlets was a crucial motor of revolution. A single subversive text in whatever form, in the hands of a single literate individual, was sufficient to spread revolutionary ideas to a whole-already discontented – community. The United Irishmen, a radical movement that emerged in the wake of the French Revolution was made up of -initially- members of the urban middle classes in Belfast and Dublin and, crucially, membership crossed the religious divide. The organisation was adept at harnessing the power of print and by 1796 newspapers were ‘universally’ read and the common people were aware of events passing on the continent. The first newspaper to be published in Ireland was the Belfast News-Letter in 1737 and the United Irishmen, founded in 1791 was quick to produce a more radical press, The Northern Star, in 1792 in an attempt to use the new media form as a tool of political education. A similar process was underway in Dublin:

‘By the 1790s in Dublin there were at least fifty printers in Dublin, thirty-four Irish provincial presses….and at least forty newspapers in print. There were fifteen booksellers and printers in the Dublin Society of the United Irishmen.’[6]

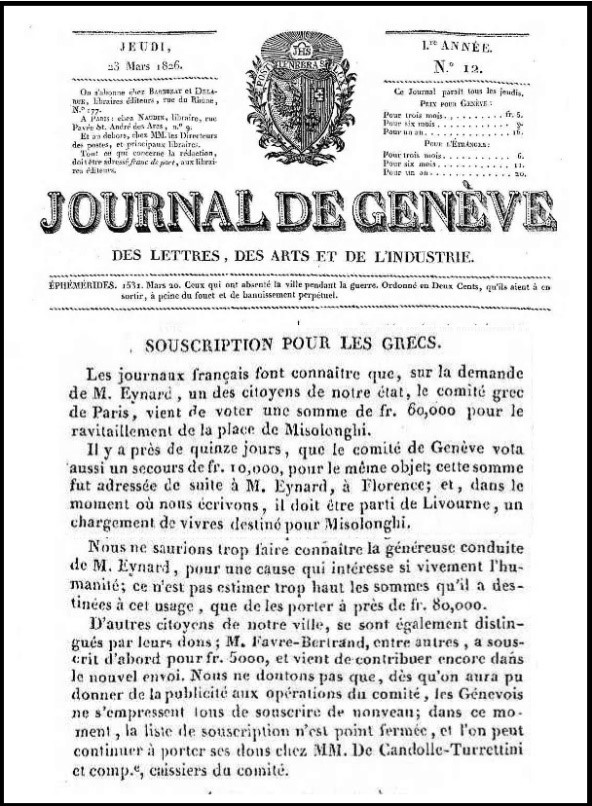

The impetus for change began in the cities of Belfast and Dublin, the latter already the ‘second city of Empire’ with more than a hundred thousand inhabitants and a centre of commerce and administration and it was through the medium of print that the movement spread to the country as a way of bringing in secret societies such as the Defenders that were initially formed to achieve agrarian reform, by force if necessary. The situation in Greece was significantly different[7]. Newspapers, initially handwritten, began to appear in Greece around 1821 with the first printing presses arriving from abroad around the same date. The first printed newspaper, Salpinx Eliniki appeared in Kalamata in August 1821 but ceased publication after three issues. It was not until 1828 that print journalism began to find its feet but again it was bedevilled by short print runs, poor circulation and political interference. The general attitude seems to have been: ‘The press is free, as long as you don’t write’[8].

The emergence of urbanisation, literacy and radicalism in late 18th century Ireland had, paradoxically, much to do with the land question. While the Ottomans were content with the extraction of taxes and rent, land in Ireland fast became a commodity to be bought and sold. In many ways Ireland was a laboratory for the testing out of the colonial project that was to expand to a global empire[9]. This was nowhere more evident than in the form developed for the confiscation and control of land. The Ottomans were colonisers in the basic form of gaining the control of land by force, but they did not, to any great extent, dispossess those who had worked the land directly under Byzantine of feudal rule. While ownership of the conquered lands was vested in the Sultan and a complex system of taxation imposed, private property in land was prohibited although the use of the land was passed from father to son[10]. This had the effect of slowing the emergence of an organized and discontented dispossessed population, as in Ireland, filled with seething resentment at their situation and liable to revolt at any opportunity[11]. As land was not a commodity under Ottoman rule there was little basis for the emergence of an urban middle class as in Ireland as a further potential source of radical ideas.

Unlike the Ottomans the English state was not in a position to retain direct control of the occupied lands in Ireland. The numerous military campaigns had nearly bankrupted the state and by the end of another military campaign in the 1690s the question became critical: how to dispose of the confiscated Irish estates to pay down the government debt[12]. In essence, the lands were offered for sale thus opening a market for land, that not only further enraged the native population- apart from those who managed, by hook or by crook, to acquire lands themselves-and created a middle class of brokers, accountants, lawyers etc. as well as an enlarged state bureaucracy and occupying military. This led to the further formation of an urban middle class and the circulation of revolutionary ideas which were to take hold in the last decade of the 18th century[13].

The objectives of the United Irishmen were radical and, however confused, pointed towards the “freedom of Ireland’ and a clear rejection of English rule. The leadership of the rebellion were mainly of the urban middle classes -both Protestant and Catholic- although artisans, weavers, printers, and other tradesmen made up a significant part of the urban membership. Support for the United Irishmen whose cause could be described as ‘Enlightenment anticolonialists’[14] crossed a broad spectrum of opinion both in Ireland and England including such unlikely figures as (Irish born) Edmund Burke -philosopher and statesman- and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, a prominent London based -and Irish born- playwright[15]. Both were Members of Parliament and Burke’s pamphlet Reflections on the Revolution in France, became a central and defining text of British conservatism.

For both the radicals and the conservatives the problem lay with the small clique of big landlords- the Protestant Ascendency[16]. From Burke’s point of view the Ascendancy, who defined themselves by religion, were the cause of the problem which could only be solved by the emancipation of the catholic population and the return of their lands. He concluded, somewhat optimistically, that this would lead them to accept the status quo. For others a successful rising would open the door to separation from England and the emergence of a Catholic middle class, stunted by the Penal Laws that forbade the ownership of land, entry into the professions and public administration and the practice of their religion although these laws were gradually being diluted from the early 1790s onwards[17].

In reality the Uprising failed. French support did not materialise to any significant extent, and the rebels, poorly armed and untrained, were no match for a British Army well-equipped with muskets, canon and mounted cavalry. Over 10,000 (at least) Irish lay dead, a number, taking into account population size, was probably more than died during the French Revolution[18].

The consequences of the failed uprising were profound. The rhetoric of independence and separation from England was now firmly on the agenda but the horrific nature of the repression of the uprising led others to push for reform rather than revolution and the mass movement for Catholic Emancipation led by Daniel O’ Connell was to dominate politics for a generation. For liberal Protestants, participants and sympathisers, the failure of the project led to a disengagement from politics. Many of them were executed, others narrowly escaped retribution and, as we will see, the majority of the Irish Philhellenes were the children of 1798, born between 1780 and 1800 to parents who were directly or indirectly involved in the uprising.

THE TWO GENERALS AND A SEA CAPTAIN: CHARLES NAPIER, RICHARD CHURCH AND GAWAN WILLIAM ROWAN HAMILTON

These three senior British Army and Naval officers all of Anglo-Irish background, played a significant part in the Greek struggle.

Charles Napier was born in London in 1782 but having moved to Ireland at the age of three spent his childhood there. His father was an Army officer of limited means but, in contrast, his mother, Lady Sarah Lennox, was extremely well connected with the English royal family being a great granddaughter of Charles the Second and King George the Third proposed marriage to her. She herself -and other members of her family- were well known for their radicalism. She attempted, unsuccessfully, to employ Jean Jacques Rousseau as tutor for her children. One of her sisters married the Anglo-Irish Duke of Leinster who was leader of the radical Patriot Party. One of their children -a first cousin of Napier- was Lord Edward Fitzgerald, a leader of the United Irishmen who died in prison during the 1798 rebellion. Another sister was married to Thomas Conolly, a catholic reform politician something that put Napier’s family at the heart of Irish radical/reform politics as they lived in close vicinity to his mansion in Celbridge, County Kildare[19]. One central preoccupation of the Radicals -that was to leave a permanent impression on Charles- was the question of agrarian reform in the interests of the rural poor. This, of course was a central issue in Ireland where the landlord class, intent on extraction of rental income had little interest in any change. Indeed, the reality was that, if a tenant improved his rented land, the landlord would increase his rent accordingly.

The family background and their radical beliefs did not hinder them from purchasing Charles a commission in the British Army at the age of eleven. This was a far from uncommon practice among upper class English families. Younger sons had no rights of inheritance, and the choice was between entering the clergy, a profession, or the armed forces[20].

As Napier rose through the ranks, his radicalism did not seem to wane as a letter to his mother in June 1816 seems to testify[21]. Yet this radicalism took second place to his role as a British Officer and colonial administrator. He was appointed in March 1822 to be military Resident of Cephalonia with the power of martial law based on the principle that ‘The natives …could not be safely entrusted with power’[22]. Here we begin to see the nature of Napier’s radicalism. As in his criticism of politicians and landlords in Ireland -and England- he blamed the power holders, but not the common people as a proper colonialist would do. He enjoyed being a despot[23].

He also wrote about the Greeks: ‘Seeing how fit and unfit such a people were for war I longed to lead them and resolved to do so. The idea constantly arose that my destiny was to command a Greek army against the vile Turkish horde’[24].

He was, in fact, offered the post of commander of the Greek forces but it all came to nothing[25]. Although Napier was a strong and vocal supporter of Greek independence, this was tempered by his imperial mind-set, as he thought that the Ionian Islands should remain under English control because of its strategic importance for control of the Mediterranean Sea. Still, his radical bent did distinguish him from the bulk of his fellow officers and when he was ordered to confront the Chartist movement in the North of England- a cause for which he had some sympathy- he seems to have managed to control the situation without restoring to violence unlike some other Generals. Perhaps his mind-set is best summed up by the following quote: ‘…. but the Greeks are more like the Irish than any other people; so like, even to the oppression they suffer, that as I could not do good to Ireland the next pleasure was to serve men groaning under similar tyranny’[26].

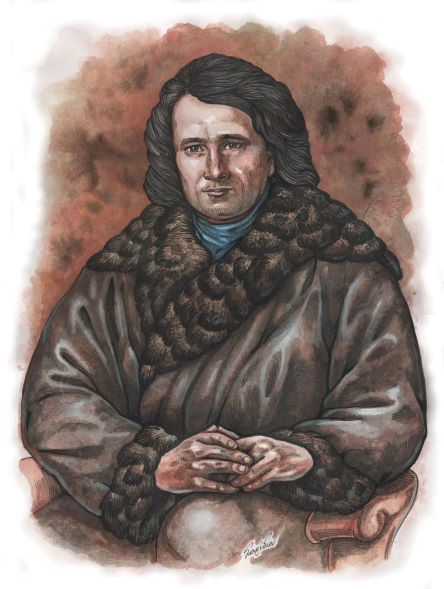

Portrait of Lieutenant General Sir Charles James Napier

GENERAL SIR RICHARD CHURCH

If information on the early life of Charles Napier is extensive and accessible, the same cannot be said for Richard Church. He was born in Cork, Ireland, in 1784 to a Quaker merchant family and left home at sixteen to join the British Army. Given that the Quakers are pacifists, this would have been very unusual and he and his family were disowned by them yet he seems to have remained an ardent Christian during his lifetime- and also had good relationship with his family.

During his first posting –at the age of sixteen- to Egypt during the Napoleonic Wars in 1801- he developed a strong regard for the Greeks and nothing but contempt for the Turks:

‘The Greeks who are slaves to the Turks and are Christians, are as opposite a people as possible, a brave, honest, open generous people…If they make any money by trade, when it pleases the Turk to take it from him, and if he murmurs, death is his redresser. Oh, how I hate the Turks’[27].

One cannot but compare his attitude towards Greeks and Turks with that of Napier. Although both were horrified by the Ottoman treatment of the Greeks, an understandable reaction given their background and upbringing[28] in a country recently devastated by a colonial power they now served, Napier seems to have been driven by ambition and lust for fame, while Church devoted his life to the Greek Cause at some personal and professional cost. He has been described as: ‘… a fiery Bible-reading Irishman with an unusually deep connection to the Greeks’[29].

Although Church was more than sympatric towards the Greek cause and spent a large part of his modest fortune in support of it, his participation was beset by problems which faced all Philhellenes unfamiliar with the reality of Greek society and politics. This involved the difficulty of dealing with the fragmentary and divisive nature of Greek politics and factional infighting, the problem of setting up a regular style army in this context and, indeed, disputes among foreign participants themselves. His success as a military commander was a mixed one, from the debacle of the attempt to rescue the Greek garrison in Athens to his successful guerrilla campaign in western Greece aimed at extending the boundary of an independent Greece that, again, was marred by political interference and political infighting.

Yet he did gain the respect of the Greeks themselves and spent the rest of his life in Athens in the house purchased from the Scottish historian, George Finlay[30]. He died in Athens on March 20, one hundred and fifty years ago. He was given a state funeral and the inscription on his monument in the First Cemetery in Athens reads:

Richard Church, General, who, having given himself and all he had, to rescue a Christian race form oppression and to make a Greek nation, lived for her service and died among her people, rests here in peace and faith.

In general, most of the members of the British armed forces who embraced the Greek cause were either Irish or Scottish. Of all the British officers who served in the Ionian Islands, the Irish were the ones who supported more the Greek cause. Along with his engineering officer, John Pitt Kennedy, who was also Irish, Church was accompanied to the Ionian Islands by another Irish born officer, Hudson Lowe[31]. When Church returned to Greece in 1827 as Commander of the Greek land forces his two aide-de-camps were Irish: Charles O’ Fallon and Francis Castle.

General Church’s portrait

General Church’s pistol

Letter of Karaiskakis accepting the appointment of General Church to lead the armed forces of Greece

CAPTAIN GAWIN WILLIAM ROWAN HAMILTON

Hamilton (1783-1834) was born in Paris and his family moved back to Ireland soon after his birth. His father, Archibald Hamilton (1751-1834) led an adventurous life particularly as a result of his membership of the United Irishmen. He was jailed for sedition in 1792. Due to his further activities in prison in Dublin, the government seemed determined to execute him. However, he escaped and managed to find a boat to take him to France. Finding little support for the Irish cause in France, he moved to America and remained in exile there until his eventual return to Ireland in or about 1804. He remained committed to radical causes and was a strong supporter of Catholic Emancipation. He continued to be a thorn in the side of the English establishment being publicly described in the London parliament as an attained traitor – by Robert Peel- and as a convicted traitor by another MP. He had ten children and his son, Gawin William, took the now familiar route of joining the British armed forces, in his case the Royal Navy[32].

Although Hamilton is passed over in most writings on the war, he did play a significant role as is acknowledged in the most recent book on this period[33]. Mazower writes: …’Gawen Hamilton is a crucially important if under sung figure in the story of the Greek revolution’. He was commander of the British squadron in the Aegean and, as a person trusted by both Greeks and Turks, was engaged in numerous negotiations with both sides. Deakin describes him, somewhat romantically, as: ‘A lovable, warm hearted Irishman from County Down and a staunch philhellene[34]. As Woodhouse has pointed out, British army and naval officers were to a large extend anti-Greek. Hamilton describes the officers in his squadron as ‘almost without exception, violently anti-Greek’. Crawley suggests that he may have considered leaving the Royal Navy and joining the Greek resistance. Given his background, one common to many of the Irish Philhellenes, this is hardly surprising.

THE WAR OF WORDS: THOMAS MOORE, JAMES EMERSON TENNANT, EDWARD BLANQUERIE AND OTHERS

James Emerson Tennant was born in Belfast in 1804, his father being a wealthy tobacco merchant with no obvious political connections. His first contact with Greece was a visit in 1824 as part of a Grand Tour that took him to France and Italy. Before his departure he managed to get letters of introduction from the Greek Committee in London and a contract from the Times newspaper to report on the course of the war. Perhaps driven by romanticism than any clear political convictions[35] on arrival in Messolonghi he joined Byron’s artillery corps- although he had no military experience- and returned to England after Byron’s death in April 1824. He returned briefly to Greece in 1825 and was appointed a captain of artillery. Again his sojourn was a short one yet his book Picture of Greece (1826) and a series of newspaper articles in English newspapers did contribute to support for the Greek struggle. Two other books followed- Letters from the Aegean (1829) and a History of Modern Greece (1830). He was to marry Letitia Tennant daughter of James Tennant a prominent -and wealthy- United Irishman[36]. He then pursued a political career and was later to dismiss his Greek activities as ‘a fit of absurd folly’[37].

In many ways Tennant moved in the same ideological world as, for instance, Napier. He was appointed Colonial Secretary of Ceylon in 1845 and tended to see the colonial project through the optic of religion. For him, Protestantism was the only true religion as the break with Catholic obscurantism created it as the religion of progress, civilization, enlightenment and sound government. This basic stance coloured his views on Ireland. On one hand he opposed slavery, supported Catholic Emancipation but totally rejected demands for a separate Irish parliament on the grounds that it would lead to what he called political popery, by which he meant a dominant role in politics for the Catholic Church[38].

Order of the redeemer and medal of the Greek Revolution offered to Sir James Emerson Tennent by King Othon, and an enamel mourning locket with Byron’s hair given to Emerson Tennent by Lord Byron’s friend Gamba

Portrait of James Emerson Tennent

THOMAS MOORE

Thomas Moore, known as Ireland’s national bard, was born in Dublin to a catholic family in 1779. He entered Trinity College Dublin in 1794 one year after permission was granted to Catholics to enter the College[39]. He was soon associated with fellow students close to the United Irishmen. Although he did not take part in the 1798 Rising, it was with the rebels that his sympathies lay and his song O Breathe Not his Name was written in memory of his fellow student and friend Robert Emmet who was executed for his part in the failed uprising of 1803. (youtube: 6 Irish folksongs op.78:l. O Breathe Not His Name).

Moore was a complex character. He supported any move towards Irish independence and although not a fervent- or even practising- Catholic was contemptuous of ‘the arrogance with which most Protestant parsons…assume credit for being the only true Christians’… and was more in favour of the things that scriptural Protestantism hated: ‘the music, the theatricality, the symbolism, the idolatry’. In this, of course his politics differed fundamentally from that of Emerson Tennant.

Moore was an early member of the London Greek Committee- although he was critical of the committee’s effectiveness[40] and it was perhaps his poetry and songs that were the most influential. Apart from his songs and poems which referred directly to Greece his Irish Melodies and Lalla Rookh, in particular, had a considerable influence on radicals across Europe from Russia to Greece and ‘helped forge political change to that of a secular harmonious society living under social democracy’[41].

Bust of Thomas Moore, Irish poet (1779-1852), impressed “Tom Moore” on the verso

EDWARD BLAQUIERE

Edward Blaquiere (1779-1832) was born in Dublin of Huguenot descent. Little is known of his family background or upbringing[42]. He joined the Royal Navy and rose to the rank of Captain seeing action in the Mediterranean during the Napoleonic Wars.

He explained his motivation for getting involved in the Greek struggle writing: ‘That he was enthusiastically favoured to Greek freedom not less from a sense of religion than of gratitude to their ancestors’[43].

Whatever one might think of Blaquiere’s methods, few would deny his influence in raising support for the Greek struggle. His meeting with Byron in April 1823 proved decisive in convincing him, Byron, to play an active role in the war[44] and he was also instrumental in convincing Jeremy Bentham to support the Greek cause and attend meetings of the newly formed London Greek Committee[45]. He soon became the driving force behind the Greek Committee holding meetings up and down the country and publishing three books and a number of pamphlets between 1823 and 1828. His writings and other activities bore little resemblance to the real situation in Greece but seen as propaganda for the cause were rather effective.

He died in a shipwreck in 1832 on a voyage to Portugal.

BLAQUIÈRE Edward – Narrative of a second visit to Greece, including facts connected with the last days of Lord Byron, London, Geo. B. Whittaker, 1825.

John BOWRING (1792-1872), signed letter addressed to the French Philhellene, 1 p. in-4. «Greek Committee”, 31 mars 1825. “I am instructed by the Greek Committee to present to you their grateful acknowledgments for the subscription of f. 200 which you have presented to their funds by the hands of capt. E. Blaquiere […]. The warm and active sympathy you have evinced in the cause of Greece is one of those rewards which, next to the permanent security of that cause, best repay them for their own exertions […]”.

WILLIAM BENNETT STEVENSON

William Bennet Stevenson, born about 1787, is generally regarded as Irish and his birthplace is generally said to be County Cork. The evidence to support this is scant and the name is not a common one in the County. However, his middle name, Bennett, is well established in Cork city.

Stevenson arrived in South America about 1803 -aged about 16- when resistance to Spanish rule was growing across the sub-continent. He spent 20 adventurous years there, some in prison as a suspected Spanish spy. It was soon clear that he was man of exceptional talents and abilities. In 1808 he became private secretary to the President and Capitan General of Quito and on the outbreak of the Ecuadorian War of Independence he joined the insurgents. In 1810 he was made Governor of the province of Esmeralda.

He then turns up in Chile as secretary to Admiral Cochrane who was in command of the Chilean Navy established by Bernardo O Higgins who led the revolt against Spanish occupation[46]. He saw active service in naval operations against Spain under Cochrane between 1818 and 1822. Both he and Cochrane returned to England about 1824. Stevenson’s three volume book on South America appeared in 1825 and was soon translated into German and French[47]. A review of the book in the Monthly Review 1825 comments on the absence of any information on WBS’s background: ‘There is a mystery about this whole commencement of Mr Stevenson’s narrative which he has yet to explain’. This would seem to indicate that little was known about him in London at that time[48].

Around this time Cochrane was recruited to organize and command a Greek Navy and he departed for Greece, accompanied by WBS arriving in Aegina in March 1827. While Cochrane got involved in fruitless negotiations with the various Greek factions- he was not known for his patience- Stevenson set about pushing for agricultural reform- famine was rife in the area- and, in particular, the establishment of potato plantations on Aegina and Apathia- directly opposite Poros. He had the full support of the Greek president, Capodistrias. Zografos, in his History of Greek Agriculture writes:

‘The Irishman Stevenson is very closely associated with the revival of husbandry in the country. He was from the very beginning a close collaborator of the Greek President who displayed a special interest in farming and his expertise was sought after by the latter in pursuit of his agricultural policy….. And we too should revere this man among the many others who had helped our country in the early stages of the young nation’s growth’.[49]

WBS was successful in establishing large potato plantations- as well as wheat and rye- in the area employing large numbers of workers. His visit was cut short by illness and in his last letter to the President in July 1828 he writes that he must return to London for ‘Health and private reasons’. Here the track goes cold; There seems to be no information regarding his life after leaving Greece[50].

CONCLUSION

What immediately springs to mind when looking at the nature of Irish involvement is the heterogeneity of those involved as a social group. Their backgrounds were broadly similar, some went to school or university together and they moved in the same social and family circles.

Their general motivation cannot be separated from their common experience of English rule in Ireland and the impact of the failed 1798 uprising. One might ask why most of those mentioned in this paper came from the Anglo-Irish class, with the exception of Thomas Moore. The avenue of social mobility enjoyed by the Protestant elite was not open to members of the Catholic population even if they had been willing to embark upon such a path. Also, politics in Ireland in the 1820s was dominated by the reform movement led by the charismatic Daniel O Connell. Hobsbawm describes the movement as unique: ‘We can in fact speak of only one national movement organized in a coherent form before 1848 which was genuinely based upon the masses’[51]. Participation in the Movement was massive and crossed all classes absorbing both radicals and moderates. It eventually led to Catholic Emancipation in 1829. There was little motivation therefore to engage directly with the Greek struggle among the general population as they were deeply involved in one of their own[52].

The motivations of the Philhellenes were complex and varied. For continental Europeans romanticism played a large part[53], something that was absent among the Irish contingent. The idea of supporting a Christian people against Ottoman and Islamic oppression is a common thread, a motivation which was rooted in socio-historical experience: in the case of the Germans the repression that followed the Napoleonic Wars and for the Irish the experience of colonial rule. The Irish in general did not share the negative attitude of others towards the Greek population but identified closely with them both culturally and politically. In short it is worth noting that the numerically inferior Irish contingent had a disproportionate effect on the course and the outcome of the War of Independence, something for which Greece will always be grateful.

Letter of Sir John Bowring to Henry Kane, Consul at Ancona, introducing “Mr James Emerson Tennent, who is proceeding to Greece with a desire of rendering their talents and exertions serviceable to the Greek cause, asking for his assistance for them, 1 side 4to., London, 1st October 1824.

Gazette de France 15/6/1827.

French and English commanders, De Rigny and Hamilton arrived in Piraeus and tried to negotiate an honorable capitulation for the Greeks but Reshid Pasha did not want to offer the slightest alternative to the Greeks. Nothing certain yet was known for the big defeat of the Greeks. Although in the beginning the first battles were positive for them, some 8.000 or more Turkish troops arrived from Saloniki and the Greeks lost the battle. Several other news.

“HOW MUCH BLOODSHED HAVE WE NOT UNWITTINGLY OCCASIONED!”

Missolonghi, “Sunday Evening” (probably 6 June 1824). 4to.3pp.on bifolium.

Autograph letter signed by Murray, Charles, Scottish traveler and Philhellene (1799-1824), martyr of Greek Independence. With autograph address. To the writer and fellow Philhellene Edward Blaquiere (1779-1832) about the grim situation in Greece during the Greek War of Independence, mentioning typhoid fever as well as poverty and starvation.

REFERENCES

[1] For the most comprehensive list of Irish Philhellenes see www.Patrickcomerford.com/2008/11/irish-anglicans-and -greek-war-of-.html?m=1

[2] Culture and Imperialism, (NY, 1993). p.78

[3] For a more extended discussion on the question of affinity and identity see Beaton, R., Greece: Biography of a Modern Nation, London, 2020, Ch.1-2.

[4] The seminal text dates from around 1188: Gerald of Wales, Topographia Hiberniae, His claims resonate down the centuries and inform English conceptions of the Irish: ‘The Irish are animalistic in their passions, sinful and ignorant in their irreligiosity, deficient in proper technological advancement, husbandry, and industry, and lacking proper human cultivation and social relations, all of which properly signal their properly subordinate status.’ See Sarah E McKibben, in their “own country”: Deriding and Defending the Early Irish Nation after Gerald of Wales, in, Eolas, The Journal of the American Society of Early Irish Medieval Studies, 8, 2015, 39-70. Hiram Morgan, Giraldus Cambrensis and the Tudor Conquest of Ireland, in Morgan, H, (ed.) Political Ideology in Ireland, Dublin, 1999.

[5] Occupation is, of course, a complex process. One feature of the original Anglo-Norman invasion was their gradual integration into Irish society forcing London to introduce legislation to call a halt to this process.

[6] Whelan, K, The Tree of Liberty, (Cork, 1996), p.63.

[7] This is not to deny that there was a considerable level of literacy among the general population in both countries. In Greece the Orthodox Church was primarily responsible for this while in Ireland it was illegal ‘hedge schools’ that kept education alive.

[8] See Argyropoulos, R., The Press, in The Greek Revolution, Kitromilides, P, Tsoukalas, Eds., (London, 2021), 2021, p496-509.The activities of Leicester Stanhope and his almost maniacal focus in bringing the newspaper(s) to Greece throw an interesting light on the diverse nature of Philhellenism. St, Clair describes him thus:.it is to Stanhope that belongs the doubtful credit of being the only man who went to Greece during the war whose political ideas were not modified by the experience, p.185ff. Stanhope was born in Dublin in 1784. His father was commander of the British Army in Ireland and he- Stanhope- joined the British Army in 1799. He had no further connection with Ireland.

[9] Morgan, Political Ideology p. 9

[10] Halil Inalcik, The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1600, (London, 1973 Ch. 13.

[11] It should be pointed out here that, like the Greeks, some Irish (mainly men, Protestant and Catholic) were not averse to contributing to the imperial cause. While the Greeks largely confined themselves to the Ottomans, the Irish were rather more promiscuous in their choice of colonial masters: they served Portugal, Spain, France, Denmark, Holland as well as England. See Ohlmeyer, Making Empire, ch.4,.

[12] See Philip Stern, Empire Incorporated: the Corporations That Built British Colonialism, (Harvard, 2023), Stuart Bell, A Masterpiece of Knavery? The activities of the Sword Blade Company in London’s Early Financial Markets. Business History, 54, 4, 2012, 623-638, Simms, J.G, The Williamite Confiscation in Ireland, 1690-1703, (Westport, 1976).

[13] English colonialism- as well as that of Spain, Holland, and Portugal used similar methods of granting charters and patens to traders and settler. Also, while the Ottomans established fortified garrisons few would later develop into large towns and cities unlike in other colonial situations.

[14] Terry Eagleton, Were does culture come from? London Review of Books, 46,8,2024, p.6

[15] Burke’s stance was a conservative one. He believed that by introducing reforms the Irish would be more likely to accept British rule. Sheridan was a more active supporter of the. United Irishmen and a close friend of Thomas Moore and part of the Byron circle. His son, Charles was an active member of the Greek Committee in London.

[16] The use of the terms Protestant and Catholic should not be taken to suggest that the conflict was about religion. It is simply the most convenient marker of difference between the two groups. In other colonial situations the main marker might be skin colour.

[17] This was fundamentally different from Ottoman policy. One exception was the ban on the ownership of horses- above a certain valve in the Irish case- probably for both symbolic and military reasons.

[18] The literature on 1798 is extensive. See Curtin, N, The United Irishmen, Oxford, 1998. Whelan, K,

The Tree of Liberty, (Cork, 1997).

[19] Basically, the difference between the ‘reform’ and’ ‘radical‘ position was that the former, while highly critical of English rule in Ireland wanted more autonomy without separation. The radicals were tending more towards separation and also embrace radical social policies such as land reform.

[20] To go into any long-established Protestant Church in Ireland is a harrowing experience. The walls are lined with memorial plaques of younger sons who died in British colonial wars most in their early twenties or younger.

[21] Napier, W, The Life and Opinions of General Sir Charles James Napier (London, 1857), p.268-9.

[22] Napier, 1857, p.305.

[23] Napier, p.306. The life of being an ‘enlightened despot’ is rather a contradictory one. He wrote that his time in Kephalonia was probably the happiest in his life. He had two daughters by a Greek woman, Anastasia. As part of his public works project he had a garden constructed as a playground for his children. It exists to this day as ‘Napier Gardens’.

[24] Napier, P. 366.

[25] St. Clair, W., That Greece Might Still be Free, (Oxford, 1972), 302-3. St. Clair’s judgement is stark: “Greece was fortunate to escape him.”

[26] Napier, p.366.

[27] Lane- Poole, S, Sir Richard Church, (London, 1890), p.6.

[28] Although, unlike Napier, little is known about Church’s upbringing it is clear that his family saw itself as Irish and two of his senior officers, Captain Charles O’Fallon (his A.D.C) and Francis Castle. Were Irish. Other members of his staff, Frances Kirkpatrick and Gibbon Fitzgibbon were also Irish.

[29] Mazower, M., The Greek Revolution, (London, 2021), p.367. Hamilton (see below) describes Church as a fine fellow, but a complete Irishman.

[30] Finlay, G, History of the Greek Revolution, 2 Vol. (Edinburgh, 1860). Finlay was rather dismissive of Church’s contribution in this book. The now restored house in the Plakta now displays a plaque devoted to Finlay although there seems to be no mention of Church having resided there.

[31] Better known as Napoloen’s goaler on St. Helena. Comerford writes that, as a tribute to his help in ‘liberating’ the Ionian Islands, the population presented him with a sword of honour. Comerford, P, Sir Richard Church and the Irish Philhellenes in the Greek War of Independence, in Luce, J, et al., The Lure of Greece, Dublin, 2007. This is a concise and informative survey of the life and times of Church.

[32] Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900.

[33] Mazower, p.279.

[34] Dakin, D, The Greek Struggle for Independence, 1821-1833, (London, 1973).,

[35] He is referred to by one commentator as a young man on the make. Wright, J, Priestcraft, ‘Political Popery’ and the Transnational Anti-Catholicism of Sir James Emerson Tennant in Whelan, N, (ed) Transnational Perspectives on Modern Irish History, London, 2015.

[36] The Tennant family were committed United Irishmen and social reformers. Letitia’s father had spent three years in a Scottish prison as a result of his activities in 1798.

[37] Wright, Priestcraft.

[38] He applied the same arguments to criticize the independence of Belgium from Holland in his book Belgium, 2 Vols, London, 1841. One wonders what he would have made of the role of the Orthodox Church in an independent Greece.

[39] Although Catholics were allowed entry they were barred from receiving “emoluments’- any form of financial or other aid and also could not become Fellows or Professors. Numbers remained small. A number of Trinity Anglo-Irish graduates did join the Greek cause: Arthur Gore Winter, Gibbon Fitzgibbon, Francis Kirkpatrick and William Scanlan were among them.

[40] Woodhouse, p.92. Woodhouse also points out that the Committee was mainly made up of Scottish and Irish members, although he is also critical of their effectiveness.

[41] O’Donnell, K, Translations of Ossian, Thomas Moore and the Gothic by 19th Century Intellectuals in

Lubin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature, 43, 4, 2019, p.102.

[42] Stanford speculates that he might have been one of the numerous children, or grandson, of John Blaquiere (1732-1812)-later Baron Blaquiere- who was part of the British administration in Ireland. If so, his influence could have eased Edward’s entrance into the RN. See Stanford, W., Ireland and the Classical Tradition, Dublin, 1976.

[43] Blaquierie, E., Narrative of a Second Visit to Greece, (London, 1825), p.116.

[44] Brewer, D, The Flame of Freedom, (London, 2001), p.197.

[45] Beaton, R, Byron’s War, (Cambridge, 2023), p.125, 128-9.

[46] O’Higgins was the illegitimate son of the Irish born Spanish officer, Ambrosio O’Higgins.

[47] A Historical and Descriptive Narrative of Twenty Years Residence in South America (London, 1825).

[48] His publisher, Hurst, Robinson and Company went bankrupt in 1826.

[49] Zografos, D.L. A History of Greek Agriculture, (Athens, 1921), p.283. Quoted in Vacalopoulos, C, Contribution of the Irish Philhellene Stevenson to the Agricultural Development of Greece in 1828, Balkan Studies, 13,1,1972, 129-155. This article describes, in some detail, the activities of WBS during his sojourn in Greece.

[50] For a short summary of his time in South America see Penny Dransart, Stevenson, William Bennett (ca. 1787-?) in Pillsbury, J., Guide to Documentary Sources for Andean Studies 1530-1900 Vol.3, 2008, 656-7.

[51] Hobsbawm, E., The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848, London 2020, p.170-1. The Chartist Movement in Britain, which had the sympathy of Napier who was sent to repress it, was another mass movement- if ultimately unsuccessful- led by an Irishman, Feargus O’Connor.

[52] The use of the word ‘catholic’ to describe the Irish is something of a misnomer. Ireland was not beset by wars of religion as in continental Europe. It suited the English to use religion as a tag for ethnic identity. In fact, the Roman Church had little power and religious observance sporadic during this period.

[53] For France, see Thompson, C., French Romantic Travel Writing, Oxford. 2012, and Germany Roche, Helen, the Peculiarities of German Philhellenism, The Historical Journal, 61, 2, 2018, 541-560.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Anderson, B., Imagined Communities, London, 2016.

- Argyropoubs, R., The Press in Kitromilides, P., Tsoukalas, C., (Eds.) The Greek Revolution, Beaton, R., Greece: Biography of a Modern Nation, London, 2020.

- Byron’s War, Cambridge, 2023.

- Bell, S., A Masterpiece of Knavery? The Activities of the Sword Blade Company in London’s early Financial markets, Business History, 54,4,2012.

- Blaquierie, E., Narrative of a second visit to Greece, London, 1825.

- Brewer, D., The Flame of Freedom, London, 2001.

- Bennet-Stevenson, W., A Historical and Descriptive Narrative of Twenty Years’ Residence In South America, London, 1825.

- Chatzopoulis, C., Secret Societies: The Society of Friends and Its Forerunners, in Kitromilides. Comerford, P., Sir Richard Church and the Irish Philhellenes in the Greek War of Independence, in Luce, J., et al., Dublin, 2007.

- Curtin, N., The United Irishmen, Oxford, 1998.

- Dakin, D., The Greek Struggle for Independence, 1821-1833, London, 1973.

- Derricke, J., Image of Ireland, 1581.

- Dransart, P., Stevenson, Willliam Bennet. ca 1787- 1828 in Phillsbury, J., 2008.

- O’ Donnell, K., Translations of Ossian: Thomas Moore and the Gothic by 19th Intellectuals in Lubin Studies in Modem Languages and Literature, 43,4,2019.

- Eagleton, T., Where does culture Come From?, in London Review of Books, 46,8,2024.

- Emerson Tennant, J., Letters from the Aegean, New York, 1829.

- History of Modem Greece, London, 1830.

- Belgium, 2vol., 1841.

- Finlay G., History of the Greek Revolution, 2 Vol., Edinburgh, 1860.

- Gerald of Wales, Topographia Hiberniae, London, 1983.

- Hobsbawm, E., Ranger, T., The Invention of Tradition, Cambridge, 1983.

- Hobsbawm, E., The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848, London, 2020.

- Inalcik, H., The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1600, London, 1973.

- McKibben, S., In their “owne countrie”: Deriding and Defending the Early Irish nation after Gerald of Wales, in Eolas, The Journal of the American Society of Early Irish Medieval Studies, 8, 2015.

- Lane-Poole, S., Sir Richard Church, London, 1890.

- Luce, J., et al., The Lure of Greece, Dublin, 2007.

- Mazower, M., The Greek Revolution, London, 2021.

- Morgan, H., Political Ideology in Ireland, 1541-1641, Dublin, 1999.

- Napier, W., The Life and Opinions of General Sir Charles James Napier, London, 1857. Ohlmeyer, J., Making Empire: Ireland, Imperialism and the Early Modern World, Oxford, 2023.

- Pilsbury, J., (Ed.) A Guide to Documentary Sources for Andean Studies 1530-1900, Vol 3, University of Oklahoma Press, 2008.

- Quinn, J., How the World Made the West, London, 2024.

- Roche, H., The Peculiarities of German Philhellenism, The Historical Journal, 61,2,2018.

- Simms, J., The Williamite Confiscation in Ireland, 1690-1793, Westport, 1976.

- Spencer, H., A View of the Present State of Ireland, Oxford, 1970.

- Stanford, W., Ireland and the Classical Tradition, Dublin, 1976.

- Stern, P., Empire Incorporated: the Corporations that Built British Colonialism, Harvard, 2023. St. Clair, W., That Greece Might Still be Free: The Philhellenes in the War of Independence, Oxford, 1972.

- Thompson, C., French Romantic Travel Writing, Oxford, 2012.

- Vacalopoulos, C., Contribution of the Irish Philhellene Stevenson to the Agricultural Development of Greece, Balkan Studies, 13,1,1972.

- Whelan, K., The Tree of Liberty, Cork, 1997.

- Woodhouse, C., Modem Greece: A Short History, London, 1991.

- Zografos, D., A History of Greek Agriculture, Athens, 1921.