Heinrich Treiber was born in 1796 in Meiningen, Germany and was of aristocratic descent. He was the son of a court pharmacist, he studied medicine at the universities of Iena, Munich and Wuertzburg, and specialized in surgery at the University of Paris.

Young Treiber was inspired by the struggle for independence of the Greeks, and he decided to go to Greece as a volunteer. On December 31, 1821, he left from Livorno, Italy, along with 36 other philhellenes, on the ship “Pegasus”, of the Zakynthian Vitalis, which was flying a Russian flag. After a twenty-day journey, they arrived in Messolonghi, to take part in the Greek Revolution.

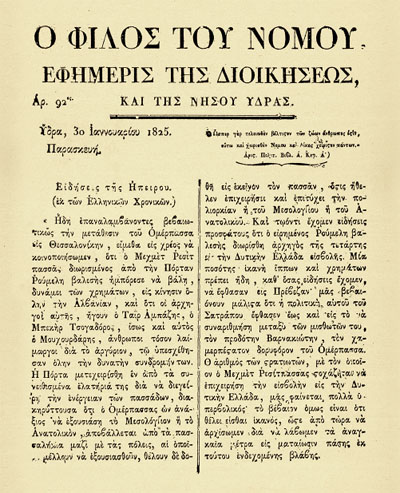

From that day on, Treiber began to write down into his personal diary everything that had happened to him over the next six years, that is, until April 23, 1828, the day he took over the management of the military hospital in Acronafplia. It is his personal impressions and judgments that reveal some, behind the scenes, of the Struggle and the role that the Philhellenes played in it. At the same time, Treiber’s diary is an important historical source for the period of the Greek Revolution.

On January 13, 1822, Treiber landed in Messolonghi, and from there he arrived in Corinth, where he became a doctor in the Regular Corps (1st Greek Heavy Infantry Regiment).

With the Regular Corps he took part in the following battles and operations:

– In Kompoti and Peta (4 July 1822). In these battles, the Regular Corps under the Italian colonel Tarella, fought along with Markos Botsaris and his corps, the battalion of the Philhellenes under the command of General Norman and the battalion of the Ionian Islands. The battle had an unfortunate end and the majority of the Philhellenes were slaughtered by the Turks. Treiber just managed to escape. However, he lost all his personal belongings and even his surgical instruments, which at that time were hard to find in Greece.

– Military operations in the mountains of Salona (1-15 September 1822), Hani of Gravia, etc.

– By order of Dimitrios Ypsilantis, the Regular Corps undertook the defense of the Great Dervenia (Kakia Skala) pass.

– He took part in the siege of Nafplion (October – December 1822). The siege was under the direct command of Nikitaras and the general supervision of Kolokotronis.

During the civil confrontations among Greeks, Treiber remained in Greece, practicing medicine in Nafplio, Kranidi and elsewhere.

– In February 1824, Treiber enlisted in the military corps organized by Lord Byron in Messolonghi, as a military doctor in the “artillery” battalion.

On April 1824 Lord Byron fell ill. Treiber was a member of the medical team trying to cure him. On 19 April Lord Byron died. Treiber undertook, with the personal doctor of Lord Byron, an autopsy and then they embalmed the body.

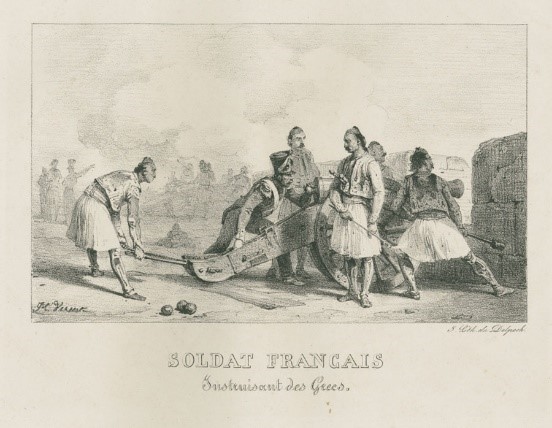

– In October 1824, the Regular Corps was reorganized by Rodios and then by Fabvier, and Treiber resumed his duties as a military doctor. He then founded a hospital in Nafplio.

– In June 1825, Ibrahim Pasha attacked Nafplio with an army of 6,000 men, but was repulsed. There were many injured, who were treated by Treiber.

– In September 1825, the Regular Corps with the new commander Fabvier attempted to liberate Tripolitsa without success. Treiber was also involved in the operation.

– In October, the Regular Corps left Peloponnese for Athens, where Treiber establishes a hospital.

– In February 1826, Fabvier began a campaign in Evia, with the Regular Corps, in which Treiber also participated. First in Chalkis and then in Karystos. The number of injured was high and Treiber treated again their wounds.

– In June 1826, Treiber resigned from the Regular Corps and assumed the position of doctor in the Dervenia military camp under the command of Karaiskakis.

– In August, Treiber leaves with Karaiskakis’ corps for the Athens area. A number of battles took place around Haidari. Treiber established a hospital in Koulouri.

– On 6 November 1826, Treiber took part in the battle of Dombraina with the corps of Karaiskakis.

– In February 1827, Treiber took part in the landing operation at Castella under Colonel Gordon, along with the corps of Makrygiannis and of I. Notaras as well as the Regular Corps, with an aim to break the siege of the Acropolis by Kioutachis.

In the battle of Analatos “1,200 Greeks and all the Philhellenes fell”, as Treiber states in his diary. He had established a hospital in Ambelakia, Salamis, to treat the soldiers, and he provided medical care to the wounded, who were transported there from the battlefield.

– On 24 April 1827, the body of Karaiskakis, who had been killed the day before in Faliro, was brought to Ambelakia. Treiber accompanied his body to Koulouri, where the funeral took place.

– In June 1827, Treiber was assigned the post of ship’s doctor on the steamer Karteria, after an invitation by its commander, the great British Philhellene Abney Hastings.

– For the next 8 months, Treiber took part in all of Karteria’s operations. Karteria plowed all the seas. From the gulf of Corinth, to the Ionian Sea, to the sea of Kythera, to the Aegean Sea and even as far as the coasts of Africa.

Together with the rest of the fleet, it patrolled these seas and imposed a naval blockade on the areas where hostilities were taking place.

– On 29 September 1827, Karteria, together with another boat, the “Sotir” and 5 other smaller ships, combatted with a Turkish fleet in the Gulf of Salona and set fire to 9 Turkish ships, including the Turkish flagship, while capturing another one (the naval battle of Agali).

– On 4 March 1828, Hastings submitted his resignation from the command of Karteria and two days later Treiber left as well. A little later, Hastings returned to his post and took part in a last operation in Messolonghi, where he was injured in the left shoulder. Unfortunately, Treiber was not there to cure him and it was too late to find another doctor, and this other great Philhellene succumbed to his injuries.

In late April 1828, Treiber became director of the Acronafplia Military Hospital (Its Kale).

When Kapodistria’s assassination took place, Treiber himself performed the autopsy and signed the relevant forensic report. He even had the sad privilege of embalming the dead body of Kapodistrias.

It is certain that this great Philhellene saved thousands of wounded and ill Greeks during the liberation struggle of 1821, in a country (Greece) where every notion of hospitalization and hospital care was at that time non-existent.

In order to describe what health services consisted of during the revolutionary period, we will use an excerpt from the work of Christos Byzantios, “History of the Regular Army”, which describes the battle of Karystos (1826), in which he himself was wounded. The only doctor there was Treiber. “The wounded,” writes Byzantiios, “advanced as best they could. Some were carried, others were helped by those who happened to be present, to reach the surgeon there. The sight of first aid offered by Chief Surgeon Treiber, was horrific. About two hundred wounded, lying on the ground in a lemon grove, moaning loudly, especially those wounded by gunfire. There was a wooden door placed on stones, used as a surgical table, on which the wounded lay. The chief surgeon, had rolled up his sleeves, and he was mercilessly cutting off the wounded members of the wounded and then wrapping them with bandage. At that moment, when I was placed myself on the bank, I saw this always worthy Philhellene surgeon, exhausted by fatigue and hunger, holding with his bloody hands and eating a small piece of bread”.

However, it was not only the provision of first aid to the wounded that concerned Treiber, but also, as Epam. Stasinopoulos states, their treatment, which usually took place in the hospitable houses of the villagers. But the villagers were accepting only the lightly injured, because there was a superstition that those who died from the wounds of the war turned then into vampires. It often took the doctor’s and the elders’ confirmation that the injured person was not going to die in order for him to be allowed to enter the house.

In 1831 Treiber married Santa Origoni, the daughter of Domenico Origoni from Corsica, and Francesca Agapiou from Athens. Origonis was a former officer of Napoleon Bonaparte, who had taken refuge in Greece since 1814.

In 1835, Treiber moved with his family to Athens, where he was assigned to organize and reform the Army’s Medical Corps, of which he became the first Chief.

Two-storey neoclassical house with gable at the crown. This is the home of the German doctor Heinrich Treiber, Asomaton Square (Biris, page 93)

Treiber participated in the design (by the architect Weiler) of the A’ Military Hospital (in Makrygiannis), and also in the design of the Municipal Hospital of Athens. He was the founder of the Military Pharmacy Warehouse.

In the foreground, the two-storey mansion with the gable at the crown was on Kriezotou and Zalokosta streets. At the center of the photo are the Old Palace, today’s Greek Parliament. Left: The Royal Military Pharmacy Warehouse 1 Akadimias Street and Vasilissis Sofias Avenue (then Ampelokipon Street and later Kifisias Street) Architects: Hans Christian Hansen [1803 – 1883] – Uprising: 1836 -1840 (Photographer: Henri Beck, 1804 – 1883).

He was one of the first teachers of the “Practical School of Surgery, Pharmacopoeia and Obstetrics” and in 1837 he was appointed “honorary” professor at the newly established University of Athens for teaching surgery.

Treiber was also appointed member of the Health Policy Congress, which defined the health policy of the country, and served as its president.

In 1842 he was appointed physician to King Othon.

Henry Treiber, portrait from the History of the Medical School. Centenary 1837-1937. National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

It is worth noting that medical science in Greece owes to the great Philhellene and scientist the introduction of anesthesiology, which upgraded treatment practices and removed pain during treatment.

On 16 October 1846, the American W. Morton administered ethereal anesthesia to a patient at Massachusetts General Hospital. A few months later, on 10 April 1847, the first anesthesia with ether was administered in Greece by Heinrich Treiber (first professor of surgery in Greece), Chief Physician, and Nikolaos Petsalis, Physician, at the Athens Military Hospital, and the press of the time deified them. Also, Heinrich Treiber administered the first obstetric anesthesia in Greece, at the Athens Public Maternity Hospital, administering anesthesia with ether to a pregnant woman together with the obstetrician Nikolaos Kostis, the first professor of Obstetrics at the University of Athens.

When the great cholera epidemic struck Athens in 1854, and the streets of the city were deserted, the great Philhellene was the only one who crossed the streets on horseback many times every day to be present at the hospital or wherever else he was called, until he was also contaminated by the disease.

Treiber continued to serve in the Army for many years, advancing to the rank of Senior Chief Surgeon, and was demobilized in 1864.

He was awarded various decorations and medals. Among them are the Greek Golden Cross (1834), the Commander (1849), and Grand Officer (1876) of the Order of the Redeemer.

Medal of the Order of the Savior, during the reign of Othon.

Treiber also received the medal of Commander of the Order of St. Stanislaus of Russia (1859), of Commander of the Order of St. Michael from the King of Bavaria (1858), the Golden Medal of the Duke of Oldenburg, and the Iron Medal of the Order of the Constitution of 3 September 1843. However the decoration, which he was most proud of, was the silver medal of Excellence of the Greek Revolution.

Silver Excellence of the Struggle, “to the heroic defenders of the homeland”, was received during the reign of King Othon to those Greeks or Philhellenes who had participated with the rank of officer in the military operations of the Greek Revolution. This medal was the highest honor

In addition to his diary, Treiber left two lists, one with 59 names of other Philhellenes he met in Greece and another one with 102 names of Philhellenes who died in action or died of other causes in Greece.

From his marriage to Santa Origoni, Traiber had six children.

His eldest daughter, Rosa, married Peter Chiappe, the son of another Philhellene who fought in Greece during the 1821 Revolution, Joseph Chiape.

He died in Athens in 1882 at the age of 86.

It is a great honor for SHP to have in its Advisory Board two descendants of this great Philhellene, to whom Greece owes so much.

Sources and Bibliography

- Αποστολίδης Χρήστος Ν. “ΕΡΡΙΚΟΣ ΤΡΑΙΜΠΕΡ ΦΙΛΕΛΛΗΝ Αναμνήσεις από την Ελλάδα 1822-1828”, Αθήνα 1960.

- Barth Wilhelm – Kehrig-Korn Max, Die Philhellenenzeit, Muenchen, 1960.

- Χρήστος Βυζάντιος (αξιωματικός του Πεζικού της Γραμμής), Ιστορία του Τακτικού Στρατού της Ελλάδος (1821 – 1832), Αθήνα, τυπογραφείο Ράλλη, 1837.

- Μαρκέτος Σπ. – Σταυρόπουλος Αριστ. Ο φιλελληνισμός της εθνεγερσίας εφ. ΚΑΘΗΜΕΡΙΝΗ 25 Μαρτίου 1988.

- Μοσχωνάς Αντώνιος. Δύο φιλέλληνες στρατιωτικοί ιατροί, Ερρίκος Τράϊμπερ και Αντώνιος Λίνδερμάγιερ. Περιοδικό Παρνασσός. τομ. ΚΘ’, αρ. 3, Ιούλιος – Σεπτέμβριος 1987.

- Στασινόπουλος Επαμ. Αι αναμνήσεις του φιλέλληνος ιατρού Ερρίκου Τράϊμπερ εφ. ΚΑΘΗΜΕΡΙΝΗ 4 Ιανουαρίου 1961.

- Γ. Δρουγολίνος, επιμ. (13 Μαΐου 1882). Έσπερος, Τομ. 2, Έτος Β’, τεύχ. 25. Λειψία.

- Εθνικόν και Καποδιστριακόν Πανεπιστήμιον Αθηνών (1939). Αριστοτέλης Κούζης, επιμ. Εκατονταετηρίς 1837 – 1937, Τόμος Γ’, Ιστορία της Ιατρικής Σχολής. Αθήναι: Τύπος «Πυρσού» Α.Ε. Ανακτήθηκε στις 25 Μαΐου 2010.

- Η αναισθησία τον 19ο αιώνα στην Ελλάδα, Αρμένη Κωνσταντίνα, Κορρέ Μαρία, Θεολογής Θωμάς, Παπαδόπουλος Γεώργιος, Αναισθησιολογική Κλινική Ιατρικής Σχολής Πανεπιστημίου Ιωαννίνων, ΙΑΤΡΙΚΑ ΧΡΟΝΙΚΑ ΒΟΡΕΙΟΔΥΤΙΚΗΣ ΕΛΛΑΔΟΣ 2011, Τόμος 8, Τεύχος 1.

- Εφημερίδα ΑΙΩΝ, Αθήνα 1882, Λόγος επιτάφιος, εκφωνηθείς εν τω Α’ Νεκροταφείω Αθηνών τη 14 Απριλίου 1882, εις τον Φιλέλληνα Ερρίκον Τραϊμπερ, υπό του αρχιάτρου Περικλέους Σούτσου.

The letter states:

The letter states: